The details of the following story are taken from this book by Thomas McInnis, a political science professor at the University of Arkansas:

(Also, the story was all over the news.)

Remember those anthrax attacks just after the attack on September 11, 2001? The federal investigation into those attacks took investigators to hundreds of scientists in the field of biological weapons. Dr. Steven Hatfill was among those questioned by the FBI. Hatfill took and passed a polygraph test that showed he had no involvement in the attacks.

Because the FBI needed clues, they offered a reward to members of the scientific community who could provide leads. One researcher had a theory that the person responsible was opposed to her campaign to get the US to agree to monitor biological weapons. She decided that Steven Hatfill fit the profile so she pointed her finger at him.

At first, the FBI ignored her but they were feeling public pressure to come up with a suspect. Hatfill agreed to have his apartment searched. When the FBI showed up, the media had been alerted and his home was surrounded by news media vans and news helicopters. The investigators found nothing, but Hatfill suffered public humiliation. Their only “evidence” was a person’s suspicions, but, even after the search carried out with Hatfill’s permission turned up nothing, the FBI obtained a search warrant and showed up again to search. Once more, there was great media fanfare.

One DOJ employee placed a call to Lousiana State University, where Hatfill was about to start a well-paid job. The DOJ employee warned the university not to hire Hatfull. As a result of the phone call, the university terminated Hatfill’s employment.

On August 6, 2002, with no real evidence, Attorney General John Ashcroft appeared on national television and named Hatfill as a “person of interest.” The government intensified its surveillance of Hatfill. He was followed by a caravan of 5 to 7 agents anywhere he went.

The harassment of Hatfill continued until the fall of 2003 when he filed a federal lawsuit. He claimed a number of constitutional violations. Among his claims was that the Department of Justice violated its policies prohibiting public disclosures about individuals being investigated.

The government, which admitted no liability, agreed to pay more than $5 million to settle the case. Hatfill was never charged with a crime.

In a written statement after the case settled, one of Dr. Hatfill’s lawyers said, “We can only hope that the individuals and institutions involved are sufficiently chastened by this episode to deter similar destruction of private citizens in the future and will all read anonymously sourced news reports with a great deal more skepticism.”

Why am I telling you this? Last week, in a series of blog posts, I addressed the problems of legal punditry and the misinformation that swirled around the DOJ investigation of the January 6 attack in 2021 and 2022. In fact, if you’re on a desktop, in the right margin of this website, you’ll see this:

Democracy requires adherence to facts. Because of the current information disruption, facts get lost in a firehose of lies, misunderstandings, speculations, and opinions. This creates misinformation-outrage cycles, which then activate authoritarian impulses in ordinarily pro-democracy people, thereby endangering democracy.

What do I mean? Click here and begin reading.

If you missed my series from last week, keep in mind the story of Steve Hatfill and begin reading here.

* * *

The Trump criminal trials are in the stage of pretrial motions. (The Manhattan civil fraud case, on the other hand, is in full swing.)

Most of the pretrial motions filed so far by Trump and his pals are slam dunks in the This Will Lose department. Only two motions so far raise interesting issues: Trump’s appeal of his D.C. gag order and Mark Meadow’s attempt to remove his case from state court in Georgia to federal court. More on those in a future blog post.

Trump’s deadline to submit suppression motions is next month. A suppression motion is filed by a defendant to keep damning evidence away from the jury.

“Wait, what!?” you exclaim. “Get rid of evidence?!” Yup. As a defense lawyer, one of the first things I did was read the government filings and disclosures closely to see if there was any evidence I could get rid of. Obviously, the easiest way to turn your client’s losing case into a winning case is to make sure the jury never sees the evidence.

Before you roar that this is a miscarriage of justice, let’s talk about the Fourth Amendment and the exclusionary rule. The full text of the Fourth Amendment is here:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

The Fourth Amendment is important because the degree of freedom given to law enforcement determines what kind of society we will live in. (Prosecutors are part of law enforcement.) One constitutional scholar called the rights enshrined in the Fourth Amendment “the centerpiece of a free, democratic society.”

Uncontrolled search and seizure is one of the first and most effective weapons of any autocratic government or dictatorship. Searches can be weaponized against the citizens. On the other hand, if not enough power is given to law enforcement officers, they will be hindered from detecting and stopping crimes.

Finding the proper balance is not easy.

A question not answered in the Fourth Amendment is how the rights of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, and papers are to be enforced.

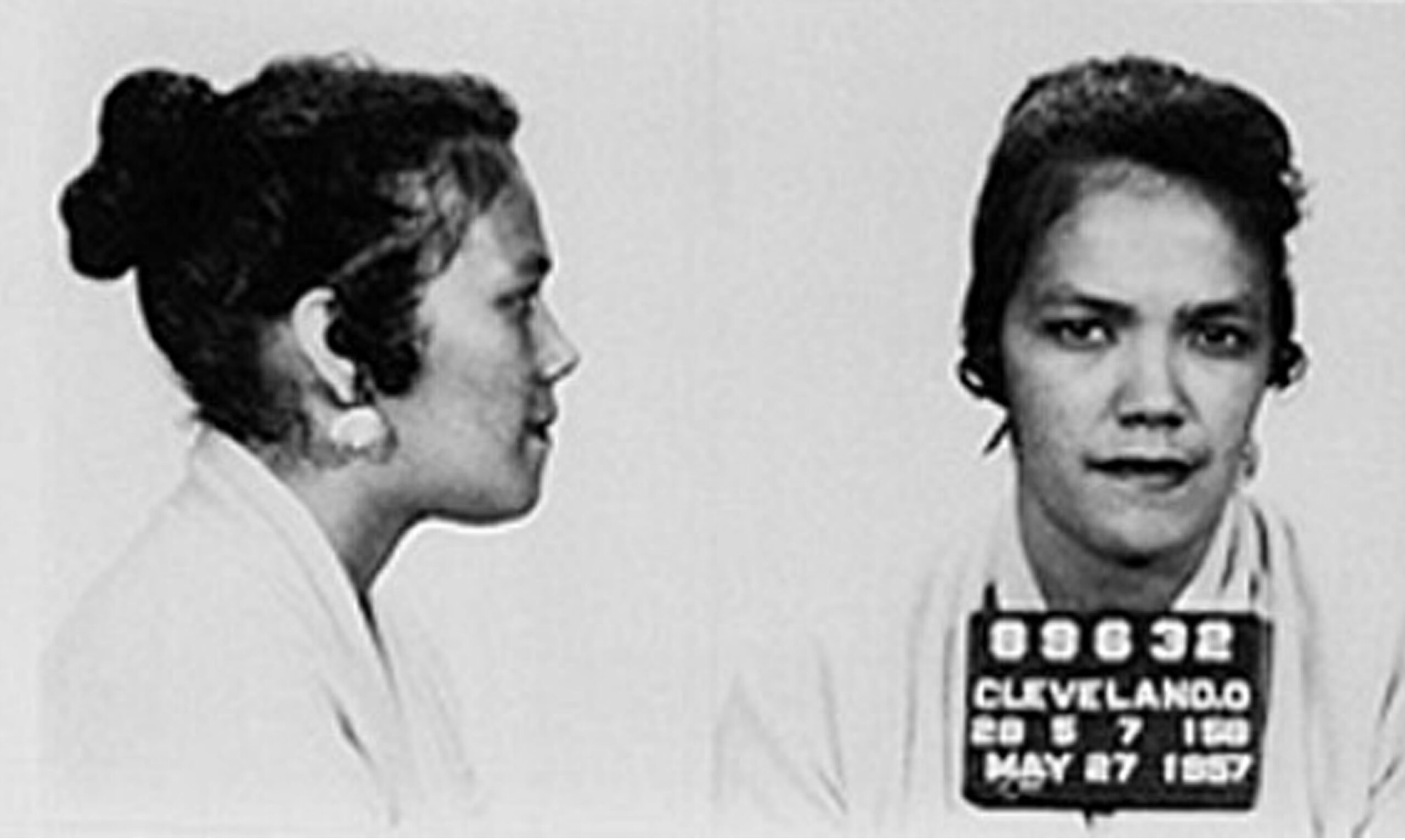

Let’s start with the story of Dolltree Mapp.

At 3:00 a.m. on May 29, 1957, a bomb exploded on the front porch of a suburban home in Cleveland, Ohio. The Cleveland police received a confidential tip that a person named Virgil Ogletree had something to do with the bombing and he was hiding in the home of Dolltree Mapp (Dolly). The confidential informant also told the officers that there was a “large amount of policy paraphernalia” (whatever that is) hidden in Dolly’s home. Dolly was known to the Cleveland police because she had a previous misdemeanor conviction for illegal gambling.

The police arrived at Dolly’s home and demanded to be allowed in. She called her lawyer. Her lawyer told her not to let the officers in unless they had a warrant, so she locked the doors and refused to open them. The officers advised headquarters of the situation and began surveillance of the house.

Three hours later, four more officers arrived. Again, the officers demanded to be admitted. Dolly refused. By then her lawyer had arrived and was observing the scene. The police officers went to the back door. One officer tried to pry open the screen door. Another tried to kick in the door. He then broke the glass in the door, reached in, opened the door, and allowed the other officers inside.

Dolly was halfway down the staircase leading to the upstairs unit where she lived with her young stepdaughter when she confronted the officers and demanded to see the search warrant. One of the officers held up a piece of paper and claimed it was the warrant. Dolly grabbed the paper and shoved it into the front of her blouse. A “struggle ensued” and the officer “recovered” the paper. Because she resisted the officer’s attempt to remove the paper from her clothing, the officers handcuffed her.

Handcuffed, she was forcibly taken up the steps into her bedroom where the officers searched a dresser, a chest of drawers, a closet, some suitcases, a photo album, and her personal papers. They also searched the child’s bedroom, the living room, the kitchen, and the basement of the building.

In a basement unit, they found Virgil Ogiltree. Also in the basement, they found a locker containing obscene books and pictures. Dolly and Vigil were taken to the police station.

After questioning Virgil, the officers concluded that he had nothing to do with the bombing and they let him go. However, they charged Dolly with possession of lewd material. At the time, Ohio had a law forbidding the possession of any “obscene, lewd, lascivious book, magazine, pamphlet, or paper.”

At Dolly’s trial, the police officers were not able to demonstrate that they had a warrant or explain why they didn’t try to get one, but based on the evidence they seized, Dolly was convicted of possessing lewd material and sentenced to serve a minimum of one year in prison.

Obviously, lots of things went wrong here. If there was a warrant, and it described with peculiarity what the officers were looking for and what they expected to find, it would have authorized the officers to look for Virgil Ogiltree, and he would not have been hiding in Dolly’s scrapbooks and personal papers. According to the anonymous tip, Dolly also had “policy paraphernalia,” which is vague at best. Possessing “policy paraphernalia,” whatever that means, is not a crime so the police officers had no business looking for it.

To solve the problem of how to enforce the rights in the Fourth Amendment, Courts created what is called the exclusionary rule, which states that if the evidence was procured in violation of a person’s constitutional rights, the evidence must be excluded at trial. The remedy is intended to be harsh enough to deter police officers from conducting unreasonable searches. This means, of course, that if the only evidence against a suspect was seized in an unreasonable search, the person walks free.

Essentially the courts have to balance two crimes—the crime an individual may have committed and the crime of law enforcement officers ignoring the Constitution. They have to decide which is more serious.

In the case of searches and seizures, courts have decided—with some exceptions—that a government officer violating the Constitution is more serious than a citizen violating the law.

The exclusionary rule has been the subject of much criticism from those who believe the remedy—letting a guilty person walk free—is worse than police conducting an unreasonable search, particularly if the crime being investigated is a serious one. In some cases, the cost of applying the exclusionary rule was so high that courts have tried to find ways to avoid applying it.

One person suggested to me that the courts should make exceptions for serious crimes. There are two problems with that. First, it would signal to law enforcement that they can disregard constitutional rights if the crime is “serious.” Second, who decides whether the crime is serious? Different people will have different ideas.

The exclusionary rule basically means that if law enforcement officers want to make sure that all evidence against a person is admissible in court, they must take care to honor the Constitutional rights of the citizens.

Dolly Mapp appealed. Her appeal was mostly about her First Amendment rights: She claimed she had a First Amendment right to possess material considered by the state of Ohio to be “lewd.”

In 1961, the United States Supreme Court agreed to hear her case. The Supreme Court decided her case on Fourth Amendment grounds. The Supreme Court held that the search of her home was unreasonable and that the evidence had been obtained in violation of her rights. The evidence was therefore excluded. Without the evidence, there was no case against Dolly, so her conviction was overturned.

The fact that Dolly’s case raised both First and Fourth Amendment rights is interesting because historically there was an overlap between the rights protected by the First Amendment and the rights protected by the Fourth Amendment. During American colonial days and earlier, the only way for the king’s officers to find out who was disseminating seditious material was to search homes and offices. While it was possible to catch people distributing material or reading it, this didn’t always enable officers to get to the source of the problem: Which printing presses were producing the seditious material and who was writing it. For this, searches were necessary.

To ensure that British citizens did not read materials that the government designated dangerous, British officers could obtain warrants to search homes on nothing more than a hunch or a suspicion. They were thus given almost unlimited powers to search private homes and offices.

In the view of the king, sedition was serious enough to warrant intrusion into people’s private homes and offices.

In 1696 the British Parliament passed the Act of Frauds. This law gave British officers in the American colonies the power:

“to enter, and go into any House, Shop, Cellar, Warehouse, or Room or other Place and in Case of Resistance, to break open doors, chests, trunks, and other Package, there to seize, and from thence to bring, any Kind of Goods or Merchandize whatever prohibited and uncustomed.”

Over the coming decades, British officers relied on the Act of Frauds to raid the homes of American colonists. The American colonists didn’t like it one bit, and we know how that ended.

When the thirteen newly independent states were considering whether to ratify the Constitution, those who argued for a bill of rights warned that without guaranteeing the rights of persons to be free from unreasonable searches, Congress would have the power to pass laws allowing unreasonable, baseless, and intrusive searches and seizures.

Fourth Amendment Jurisprudence Today

The law is a mishmash of rules with lots of exceptions, and exceptions to the exceptions.

This is because each situation is different, but we need rules. Without rules, cases will be decided based on the whim of a judge, which is contrary to the demands of rule of law.

During the years since the Supreme Court rendered a decision in Dolly Mapp’s case, courts have carved out exceptions to when the exclusionary rule is to be applied. To take one example, under the good faith exception, if the evidence is obtained by an officer who reasonably relied on a search warrant, the evidence is admissible even if the warrant later turns out to be invalid.

Careful investigators take great care to make sure their cases are not embroiled in appeals that might result in all their work being lost.

In Trump’s case, in addition to routine searches of electronic and other records, the DOJ seized the phones and conducted searches of phones belonging to lawyers and members of Congress, which requires additional hurdles because special privileges apply.

Here’s what all of this means, in practical terms

Some crimes are committed in public. Some crimes are committed in private. The crimes committed in public (like bank robbery) are easier to solve than the crimes like the kind of fraud that Trump is on trial for in New York. Crimes committed in public do not invoke the Fourth Amendment, which concerns a person’s right to privacy. With financial crimes, most of the evidence is buried in private documents. Not all inaccuracies on loan documents, bank forms, and tax records are crimes because people do make mistakes. Sometimes just proving that numbers were inaccurate isn’t easy.

The difficulty of detecting crimes committed in private applies to other kinds of crimes as well. If domestic violence occurs in a mansion surrounded by a large gated yard, it is less likely to be detected than domestic violence committed in an apartment complex with paper-thin walls.

To take another example: Solving a murder is easier than proving that a murder-for-hire arrangement happened in private, particularly if the plotters took steps to hide their arrangement.

Aren’t you glad you asked?

Do I think any of Trump’s suppression motions will succeed? No, because everything I have seen indicates that the DOJ was careful in how it gathered evidence.

But I expect Trump’s lawyers to comb through and hunt for any arguments they can raise to suppress damning evidence because that’s what defendants do.

Thank you.

Fascinating, Teri.

Can we perhaps expect a novel from you on Dolly Mapp?

I continue to learn so much from you, but I’m not ready to thank the former president for creating this opportunity. So all thanks go to you.

I’m so glad that I’m a subscriber to your posts! I learn something new every day, and I’m starting to be more patient with the proceedings.

This is an important topic to understand as regards to why investigations and prosecutions take so long. One often hears complaints about prosecutors being “too careful” or taking “too long” in preparing for major prosecutions, particularly when it comes to Trump, and others, in matters related to January 6 or other crimes.

The restrictions imposed by the Fourth Amendment–and other details having to do with rules of evidence–force investigators and prosecutors to be meticulous in the extreme. Far worse than waiting until DOJ has done its careful best would be for DOJ to assemble a compelling case, but make a mistake with the evidence such that a conviction is thrown out–or is impossible to obtain.

Too many people seem to want indictments whether there is a trial or not.

And now that there have been indictments (“not enough”, they say, or “the wrong crimes charged”), too many people want a fast trial, whether there’s a conviction or not.

The American justice system is intentionally designed to be slow and cumbersome, from the beginning of an investigation up until the end of the last appeal. (Yes, the system is imperfect and justice is too often unequally applied; the way to fix that is not to make it worse.) If you’re ever improperly charged for a crime you didn’t commit, you’ll be happy there are so many safeguards. And unfortunately, there’s no safe way to determine beforehand that you committed the crime, so as to be able to remove those clumsy safeguards when they’re “not needed” because your guilt is “obvious.” To do so invites official abuse.

Excellent comment! thx!

Thanks, Teri–you’re a really good teacher, and a really good storyteller–I realized I was on the edge of my seat during the story of the search of Dolly Mapp’s house!

Nitpick that may or may not be in the original quote:

https://twitter.com/bruckorb/status/1723752050717286429

Thank you Teri for your very clear explanation.

Thank you for your work.

Policy paraphrenalia could be gambling paraphrenalia.

Here is a link:

https://www.americanbluesscene.com/2015/09/language-of-the-blues-policy-game/

Interesting, thanks.

‘Policy’ is definitely another name for the numbers racket. Paraphernalia could have been betting slips.

See what I learned?

That information wasn’t included in the court decisions, but by the time the decisions were handed down, the gambling part was not an issue.

Teri, I always feel we are colleagues chatting. It all seems so simple when you explain it. You really have a gift.

Entertainment doesn’t help our understanding of the 4th Amendment either. I’m old enough to remember when the climax of an Adam 12 episode was reading the arrestee his Miranda rights. (I know the 5th, but bear with me). Or was it Dragnet?

Now we’ve got shows where the investigator is questioning someone in a poorly lit room & from across the room says “I notice some blood in the links of your watch. I need to test that..” 1, no-one has eyesight that good. But 2, get a warrant! In the real world, that evidence would be illegally obtained & the whole case would fall apart. (Usual caveats apply about having adequate legal representation, LE not being corrupt (Illinois, for ex), etc)

Excellent piece, thank you. I hadn’t realized there were so many nuances to the Fourth Amendment.

It is interesting how the myriad Trump cases are providing such a classroom for the public to learn far more about the nuances of the law than ever before thanks to the ongoing efforts by you, Joyce Vance, Ray Kuo, and so many others. Just reading the Constitution alone, it seemed much simpler before thinking through all of the ramifications.

I was thinking the same. Reading Teri is like returning to Uni, she takes the most complex and presents it in the most digestible manner. Fascinating information presented by a fascinating teacher.

Do you suppose we will be eligible for some classroom credits?

Thank you for this great briefing.

Especially when horrific or heinous crimes are concerned, Fourteenth Amendment protections frustrate us all. But, as you say, the offsetting balance between (A) convicting the innocent or (B) freeing the guilty, based on the originating ambitions, that motivated our American democracy, ought to lean toward (B).

Maybe in a similar way, the Conservative determination that (B) nary even one “Welfare Cadillac Mom” ought t get to parade around town in a luxury sedan, even though this proscription costs (A) millions of other families some direly needed welfare benefits, (C) amplifies why Conservatives generally don’t serve American legal/political values well, and (D) why the H*ll Republicans oughtn’t be permitted to get anywhere near-enough to run our government.

Regards,

(($; -)}™

Gozo

Teri, you have an extraordinary gift for clarifying the law. Thank you for sharing with us.

Bill