I am updating this page with new analysis of the new briefing that has been filed. Since I wrote this page, the following briefs have been filed:

- Trump’s brief is here (January 18).

- An Amicus Brief filed by 17 members of Congress is here (January 18).

- An Amicus Brief by a group of election lawyers is here.

- A whole bunch of others !!

- The oral arguments

The new sections are marked in red and with this symbol:

🆕 🆕 🆕

If you’ve already read this page (and remember what’s on it) just scroll to the new stuff. There’s a lot here, though, so for the best grade on the Teri’s Blog Constitutional Law Exam, you should review.

* * *

The Supreme Court will consider whether Colorado can remove Trump from the ballot under section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Oral arguments are set for February 8 with briefs due beginning on January 18.

Here is the petitioner’s appeal to the Supreme Court (The Republican State Committee filed a writ of cert) (December 27)

Here is the response to the petition. (January 4)

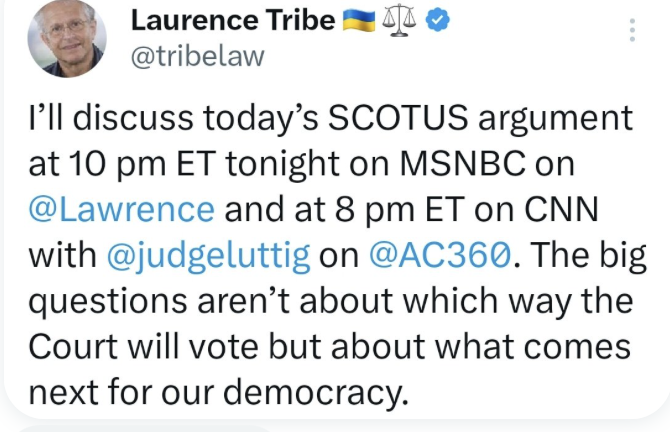

If you listen to certain commentators, you’ll think this is an easy issue. Larry Tribe, for example, who often appears on TV and in print to offer his commentary, said the argument to keep Trump off the ballot was “unassailable” and that it is backed up by “ironclad research.”

Headlines, like this one from The LA Times, told us that if the Supreme Court let Trump win, it will be “ignoring the Constitution.”

In law school, you learn to see both sides of the argument. This is particularly important for defense lawyers, whose job is to read the indictment and scrutinize the prosecutors’ case looking for weakness. Think of defense lawyers as would-be party-spoilers.

With that intro, let’s get started.

Can individual states keep Trump off the ballot under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment?

The 14th Amendment, added to the Constitution after the Civil War, includes this provision:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

The provision was intended to keep Confederates out of the federal government, but is not limited to Confederates. We know that because the word “confederate” doesn’t appear. It’s a general provision applicable to those who incite an insurrection.

In 1869, the Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase issued conflicting opinions about Section 3. First he said that it wasn’t self-executing and then he said it was. (In this context, Self-executing means that you don’t need federal legislation to enforce the provision.)

For the sake of argument, let’s assume that section 3 is self-executing and no federal legislation is needed to enforce the provision. (The Supreme Court may find otherwise).

Immediately after the Civil War, during the Reconstruction Era, federal prosecutors brought civil actions in court to oust officials linked to the Confederacy. In a few cases, Congress took action to refuse to seat Members. In other words, section 3 was used to prevent people who had won election from taking office.

These challenges ended with Congress enacted the Amnesty Act in 1872, forgiving former Confederates.

Question #1: Does the 14th Amendment bar someone from appearing on a ballot?

Look at this sentence, which appears at the end of section 3:

But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

In other words, even if a person did engage in an insurrection (or gave aid and comfort to insurrectionists) under the 14th Amendment, Congress has the power to remove that disability.

It seems to me that the fact that this provision exists implies that even if someone engaged in an insurrection, they could run for office under the 14th Amendment and hope that Congress will remove the disability.

In other words, a decent argument can be made that the 14th Amendment, by its very terms, cannot bar someone from running for office and therefore, cannot keep a person off the ballot.

In fact, the only instance of section 3 being used since 1869 to keep a person out of office happened using a lawsuit after the person was in office. It was not used to keep the person off the ballot.

Trump made that argument in his brief. (Click here and scroll to page 31.) It’s easy to make fun of the stupid parts of Trump’s filings, but it seems to me that particular argument wasn’t stupid.

I am not saying Trump will win on this. I am saying it is not a stupid argument. In fact, I think it has merit.

But Teri! What about Hassan v. Colorado?

In Hassan v. Colorado, a guy named Abdul Karim Hassan was a naturalized citizen who wanted to run for president. The problem, of course, is that the Constitution says you have to be born in the United States to run for president. After the Colorado secretary of state told Hassan that he can’t be on the ballot, he sued alleging that the Fourteenth Amendment privileges and immunity clause and equal protection clause means that he can run for president.

In other words, he argued that the Fourteenth Amendment privileges and immunities and equal protection clauses supersedes the Constitutional requirement that a person must be born here.

The Supreme Court said nope: If you’re not born here, you can’t be president. The Supreme Court then sided with Colorado and held that Colorado had the right to protect the integrity of its elections by keeping someone off the ballot who clearly is not eligible under the Constitution.

The difference is that section 3 offers a mechanism for Congress to remove the disability of engaging in an insurrection or giving aid and comfort to an insurrectionist, while the Constitution does not offer a mechanism for removing the “born here” requirement.

Given that section 3 allows for the removal of the disability, it is not clear to me that Section 3 applies to who can run for office. It applies to who can hold office. This means that Section 3, by its own terms, cannot keep Trump off the ballot.

Maine and Colorado applied state law as well as Section 3

The situation gets more complicated because both Maine and Colorado reached their decisions under a mix of state law and section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

States can enact their own laws. The Supreme Court steps in only if the law runs afoul of the Constitution.

The Colorado Supreme Court, in reaching its decision that Trump was not qualified to be president and therefore not qualified to be on the ballot, said this:

(Incidentally, the Colorado courts applied the clear and convincing standard of proof, which strikes me as the correct choice. At the same time, there was no jury and the Constitution makes a lot of noise about juries: We have the right to juries in both criminal and civil cases.)

Here is what the Maine secretary of state said:

California elected to keep Trump on the ballot. California Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis sent a letter to Secretary of State Dr. Shirley Weber on Dec. 20 calling for Trump to be removed from the ballot. She refused and announced that Trump remains on the ballot. As far as I know, she hasn’t explained her reasons.

The deep red states have not weighed in, but I think we can assume that, if asked, they would say Trump is qualified, and they would get there by defining “insurrection” and “engaged in” in a manner that wouldn’t apply to Trump’s behavior on January 6.

So, can states come to different conclusions?

As one of my readers said on Mastodon, allowing different states to come to different conclusions about whether Trump is qualified to be president is not the same as different states having different election procedures. Two different ways of conducting an election can both be acceptable. But allowing different states to come to different conclusions about whether Trump is qualified to be president under section 3 is like finding that “the cat is both dead and not dead.”

In other words, even if states can reach their own conclusions about whether Trump can appear on their ballots, someone has to decide for the nation as a whole. After all, the provision that allows Congress to remove the “disability” assumes that someone has to decide whether the disability exists in the first place.

So? Who decides?

Stephanie P. Jones (a lawyer who you can read about here) asked a few questions on social media. You can read her questions here. Jones was one of the lead authors of the Congressional January 6 report, so she knows exactly what Trump did on January 6.

I spent some time thinking about her questions. If you read her questions, you’ll see that one issue she is getting at is: Who decides whether Trump incited an insurrection?

Here are a few approaches that do not work:

-

- “I, Jane Citizen, read the Constitution, watched the clips from January 6, and read the January 6 report. It’s obvious that Trump incited an insurrection. That means he is disqualified under section 3. End of story.”

- “We all know he’s guilty, therefore, he’s not qualified under Section 3 of Amendment 14.”

I assume that why the above do not work is self-explanatory. Due process means that there is a procedure for deciding, and rule of law means that the same procedures apply to everyone.

This comment came to me on social media:

The Supreme Court needs to tell us if Trump is eligible to be on the ballot under the 14th Amendment.

Here’s the problem with that: The Supreme Court is not a trier of fact. The Supreme Court decides questions of law.

But Teri! Can’t the Supreme Court just affirm Colorado’s fact-finding?

Here is how appellate courts (including the Supreme Court) operate:

Two different states can come to different conclusions that are not “clearly erroneous,” for example, if they define “insurrection” differently.

But they can’t both be right. Trump can’t both be eligible under section 3 and not eligible under section 3.

In other words, two different conclusions can be not “clearly erronoeous,” particularly if they define “insurrection” different, but they can’t both be true. The cat can not be dead and not dead.

Someone has to decide for the entire nation.

So. first, we need a definition of “rebellion” and “insurrection” under the 14th Amendment

The Colorado Supreme Court offered this definition:

Insurrection or rebellion under the Fourteenth Amendmetn Section 3 is a “concerted and public use of force or threat of use of force by a group of people to hinder or prevent the U.S. government from taking the actions necessary to accomplish the peaceful transfer or power in this country.”

One thing the Supreme Court should do is either affirm this definition, or modify it.

In 2018, I received numerous comments that went like this: “Trump need to be charged with treason. I read the Mueller Report that confirmed that Russia launched an attack on our election. The Mueller report established “links” between Russia and the Trump campaign. We know Trump encouraged the Russians. “Russia, are you listening?” How is that not treason?”

The problem is how both the Supreme Court and Constitution have defined “treason.” The Constitution says this:

Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.

The “war” part has been construed by courts to mean that for a charge of treason to stick, there has to be a declared war and the person has to side with the enemy.

The founders make it difficult because they didn’t want “treason” thrown around as a weapon against political opponents.

The Constitution doesn’t define “insurrection” or “rebellion,” so we look for clues.

Clue #1: The Constitution gives the government authority for “calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.” This implies that the Supreme Court can define “insurrection” or Congress can define “insurrection” subject to the Supreme Court’s approval.

Clue #2: Congress has passed the Insurrection Act, which provides for this:

Also, this:

From that definition, you might conclude that January 6 was an unlawful obstruction against the authority of Congress. The hitch is the “ordinary judicial proceedings.”

What does that mean? I don’t know, and reasonable minds can differ, but because the statute concerns when the militia can be called, it doesn’t help us here.

In other words, we don’t have an authoritative definition of how “insurrection” or “rebellion” is defined under the 14th Amendment.

Okay, let’s suppose that the Supreme Court either agrees with the Colorado court’s definition or modifies it somewhat. Someone still has to apply the facts to the law. Who? The Supreme Court? If so, how will the Supreme Court do this without weighing evidence? (Appellate courts do not weigh evidence.)

Colorado? This would mean that Colorado can decide for everyone.

So, who decides?

Congress? (Imagine Marjorie Taylor Greene and Jim Jordan in charge of the Congressional committee. Scratch that idea.)

What about the fact that a majority of Senators found that Trump incited an insurrection during his second impeachment trial? Should that be enough? (If so, imagine handing that power to 51 Senators. The moment the Republicans hold a slight majority in both houses, they can disqualify any Democrats they choose, particularly because the Supreme Court doesn’t have the authority to overturn the finding of a Senate trial.)

Should a criminal conviction be the determining factor?

Historically, a criminal conviction wasn’t necessary under section 3. Moreover, I think using a criminal conviction as the standard would be a terrible idea. I have seen juries do crazy things in criminal trials and I don’t think twelve random people should be able to make a finding of guilt that binds all the rest of us. Imagine this in a deep red state: “We, the jurors, find that the protests were an insurrection and Biden gave aid and comfort to the protesters, therefore, Biden is not eligible to run for office.” Does this mean he is barred from office unless 2/3 of both Houses remove the disability?

I think we can safely assume that in the current polarized environment, 2/3 of both Houses will never agree to anything.

That’s why we need a procedure for how section 3 is to be enforced. The question is: What should the procedure be?

I don’t know. Moreover, I do not know what the Supreme Court will do and frankly, neither does anyone else. I do, however, believe that the issues are not as simple and straightforward as some would have us believe.

The Spirit of Liberty

Learned Hand (that really was his name) has been called “the greatest American judge to never sit on the Supreme Court.” Among other things, he is famous for a speech he gave during World War II. The highlights are mine, but the entire passage is worth savoring:

We have gathered here to affirm a faith, a faith in a common purpose, a common conviction, a common devotion. Some of us have chosen America as the land of our adoption; the rest have come from those who did the same. For this reason we have some right to consider ourselves a picked group, a group of those who had the courage to break from the past and brave the dangers and the loneliness of a strange land.

What was the object that nerved us, or those who went before us, to this choice? We sought liberty; freedom from oppression, freedom from want, freedom to be ourselves. This we then sought; this we now believe that we are by way of winning.

What do we mean when we say that first of all we seek liberty? I often wonder whether we do not rest our hopes too much upon constitutions, upon laws and upon courts. These are false hopes; believe me, these are false hopes. Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can even do much to help it. While it lies there it needs no constitution, no law, no court to save it.

And what is this liberty which must lie in the hearts of men and women? It is not the ruthless, the unbridled will; it is not freedom to do as one likes. That is the denial of liberty, and leads straight to its overthrow. A society in which men recognize no check upon their freedom soon becomes a society where freedom is the possession of only a savage few; as we have learned to our sorrow.

What then is the spirit of liberty? I cannot define it; I can only tell you my own faith. The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which seeks to understand the mind of other men and women; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which weighs their interests alongside its own without bias; the spirit of liberty remembers that not even a sparrow falls to earth unheeded; the spirit of liberty is the spirit of Him who, near two thousand years ago, taught mankind that lesson it has never learned but never quite forgotten; that there may be a kingdom where the least shall be heard and considered side by side with the greatest. And now in that spirit, that spirit of an America which has never been, and which may never be; nay, which never will be except as the conscience and courage of Americans create it; yet in the spirit of that America which lies hidden in some form in the aspirations of us all; in the spirit of that America for which our young men are at this moment fighting and dying; in that spirit of liberty and of America I ask you to rise and with me pledge our faith in the glorious destiny of our beloved country.

“Without bias”

I think people’s biases are getting in the way when thinking about how the Colorado case should be decided. Whatever the Supreme Court does will create a rule going forward. That rule will apply to people we like as well as people we don’t like.

“False hopes”

When Hand asks whether we rest our hopes too much upon the Constitution, laws, and courts, he is echoing James Madison in Federalist Paper #48, which you can read here. James Madison wrote Federalist Paper #48 in response to critics of the draft of the new Constitution who insisted that the three branches of government (Madison called them “departments”) must be entirely separated to prevent any one of them from encroaching on the power of the others.

Madison explained that the branches must be interconnected so that they can act as checks against each other.

He also said this about power in general: “It will not be denied, that power is of an encroaching nature, and that it ought to be effectually restrained from passing the limits assigned to it.” He went on to say that inserting phrases in the Constitution designed to restrain would-be power-grabbers won’t actually restrain a power-grabber.

If Trump is kept off the ballot and, as a result, he is not the nominee–and if, instead, a Trump sycophant wins–that person will pardon Trump of federal crimes will give him any job he wants. (He can still be appointed if he is sitting in prison in Georgia, right?) He will, one way or another, retain power given the nature of the current GOP.

My point: Beware of falling into the trap of thinking that Section 3 is an easy solution to the rise of authoritarianism in the United States.

“The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right”

It is difficult to approach these issues with humility.

Everyone likes to be popular — even former defense lawyers (who are generally unpopular). I wish I could go on social media and tell everyone what they want to hear. It would be so much fun. I’d get lots of love and “likes.”

It would also be a lot easier. Pointing out hurdles and explaining sticky issues is difficult and time-consuming.

I don’t know what the Supreme Court will do. For that matter, I’m not completely sure what the Supreme Court should do.

A few additional thoughts 🆕

(Added on January 26)

To try to imagine what the Supreme Court might (or should) do, I looked at how section 3 disqualification cases have been handled in the past. No doubt, the Supreme Court’s analysis will include looking at precedent.

Since the 14th Amendment was added to the Constitution, a total of 8 people have been removed from office under Section 3. All 8 were holding public office or had been elected to public office when they were disqualified. None were candidates for office.

#1, Kenneth Woothy, was a county sheriff, #2, William Tate, was an officer in the Confederate Army. #3, J.D. Watkins, was a state judge. #4, Zebulon Vance, was Governor of North Carolina. #5: AF Greggory, was a postmaster general. #6, John Christie, was elected to the House from Georgia.

It wasn’t clear what each of them had done, and not all were accused of violence. None were prosecuted for crimes. There were no proceedings to determine if they had engaged in insurrection. (Presumably it was understood that the Civil War was a “rebellion”😂 )

Because it was assumed that the Civil War was a rebellion or insurrection, and evidently the facts left no doubt that these 6 had engaged in the Civil War or gave aid to those who did, the procedure simply involved determining whether they should be disqualified.

- #7, Victor L. Berger. In 1919, Berger was indicted under the Espionage Act for being a socialist. After he was indicted, he was elected to Congress. Congress refused to seat him under section 3. He was convicted. Later, his conviction was overturned. After his conviction was overturned, he was elected three more times to Congress and served each term. (Sources, the Crew Doc and this piece.)

#8, Couy Dale Griffin. was serving as a county commissioner in New Mexico on January 6, 2020. While holding office, he went to the Capitol and participated in the insurrection by climbing over barriers and walls and entering a restricted area of the grounds.

Griffin was prosecuted by the DOJ for his role in the attack, was found guilty, and sentenced to 14 days in prison.

After he returned home, CREW brought a lawsuit under section 3, and a New Mexican court removed him from office under section 3.

He never appealed so we don’t have an appellate ruling.

We don’t have many examples, but of the 8 who were disqualified, each decision was made after the person was elected. The question of what constitutes a rebellion or insurrection under section 3 of the 14th Amendment has never been litigated.

Trump’s brief filed with the Supreme Court🆕

I will pick out the strongest arguments in each brief. It is a common strategy, on appeal, to include every possible argument. What matters is if any of the arguments can (or will) allow a person to win.

Keep in mind that just because an argument has merit (or is the strongest in the brief) does not mean that argument will win. If you don’t believe me, ask any criminal appellate lawyer 😂

The Best Arguments from Trump’s Brief: Colorado is adding a qualification for president.

Trump cites U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton, 514 U.S. 779, 803–04 (1995), which prohibits states from creating their own qualifications for the presidency or modifying the Constitution’s eligibility criteria. He then argues that keeping him off the ballot adds a qualification: Because Congress has the power to lift the disability at any time, Section 3 prevents a person from holding office, but not running for office.

In other words, he is arguing that the Constitution sets out the qualifications for a president, and the Colorado Election Code, which says a candidate must be qualified under section 3 of the 14th Amendment before the candidate can be on the ballot, adds a requirement to the Constitution.

In the case Trump cites, U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton, someone challenged an Arkansas election law which said that a person cannot appear on the Arkansas ballot for a third term in Congress. Arkansas insisted that it has the power to determine the qualifications for their own Representatives. The Supreme Court said nope, you can’t do that because the Constitution does not give term limits for members of Congress, and states cannot add requirements to the Constitution. The Court also said this: “A state congressional term limits measure is unconstitutional when it has the likely effect of handicapping a class of candidates and has the sole purpose of creating additional qualifications indirectly.”

The Colorado Court reasoned that, “We have the same authority to exclude a person who engaged in an insurrection as we do to exclude a person who is 28 years old.”

Amicus Briefs filed with the Supreme Court🆕

Best Argument from the Amicus Brief filed by Republican Members of Congress: Don’t take away the power given to us by the Constitution

The Republican Members of Congress argue that the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision “encroaches on Congress’s express powers by denying congress its power to remove a section 3 disability.”

You may say: “Come on, there is no way that 2/3 of Congress will agree to remove the disability,” but suppose the candidate accused of engaging in an insurrection wins the election by such an enormous landslide that there are enough members of Congress willing to remove the disability. (If it pains you to think of this happening with Trump, imagine in the future a strong Democrat is running, Mississippi declares that the candidate engaged in an insurrection based on AI generated lies. Everyone else is so enraged that they bring the Democrats into power in a landslide.)

The Members of Congress also argue that the Colorado Supreme Court’s definition of insurrection was too wishywashy and could include strong opposition to the government without force.

The brief filed by the election lawyers is weak and problematic: Stop him now to avoid a political nightmare

The lawyers make three arguments:

I. States may resolve an office-seeker’s eligibility under Section 3, and this court may review such decisions on their merits.

Argument: states have the power to determine if a candidate is eligible before placing the candidate on the merits. Colorado has the right to decide a candidate is not eligible. The court can review that decision and affirm that, indeed, the candidate is not eligible.

II. Failure to resolve the merits now would place the Nation in great peril.

Argumnet: If Trump wins the election, and the Court decides then that he is not eligible, there will be a political nightmare. So it must be resolved now.

III. The situation is more perilous than in 2000, and putting off a deision would risk disenfrancising voters (because they would have voted for a person not eligible.)

This brief (1) doesn’t address the strongest arguents made by Team Trump and (2) asking the court to make a decision to avoid a political nightmare seems problematic to me because it seems to me they are asking the court to make a legal decision based on political considerations. This makes sense, of course, if you assume that (1) is correct. But it may not be.

Literally dozens of new Amicus Briefs have been filed. You can see them here.

Analyzing each will take too long. Most contain arguments that are fairly weak. So instead, I looked through a bunch of them, made list of the arguments raised and evaluated the strength of each.

- The president is not an officer, therefore, section 3 of the 14th Amendment doesn’t apply to the president. (Somewhat weak but arguable)

- Section 3 of the 14th Amendment is not self-executing. (Somewhat weak but arguable)

- Trump did not engage in an insurrection. (Weak, but we need to know what “rebellion or insurrection” means under this section.)

- Unfit people should be disqualified. (Very weak. Introduces a new and vague standard.)

- From the time of the Civil War until now, states have enforced Section 3 under their own laws. (This one isn’t bad. The problem is that the only example available is New Mexico, which has nothing to do with national elections, and an action in Georgia against Marjorie Taylor Greene, which failed.)

- Whether Trump engaged in an insurrection is a political question to be decided by the voters. (Extremely weak.)

- Trump didn’t engage in an insurrection because his speech was protected by the First Amendment. (Weak. He did more than talk.)

- The procedure used by Colorado was an administrative procedure and should have been a trial with a jury. (This has some merit.)

Conclusion: The strongest argument Trump made is that he cannot be kept off the ballot because, unlike other disqualifications, the Constitution gives Congress the power, at any time, to lift the disability. Requiring that the disability be lifted before a primary adds an additional qualification, which is forbidden by U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton, 514 U.S. 779, 803–04 (1995).

- From all of this, here is a course of action open to the Supreme Court:

(1) Define insurrection so everyone is clear on what definition applies. (2) Deny states the ability to keep Trump off the ballot. This means that if Trump wins the presidency, an action would be filed, preferably in federal court, to determine whether he engaged in an insurrection. If a court then determines that he did engaged in insurrection, he can appeal and he can ask Congress to remove the disability. If the issue is not resolved prior to inauguration day, Section 3 of the 20th Amendment applies until the issue can be resolved:

. . . If a President shall not have been chosen before the time fixed for the beginning of his term, or if the President elect shall have failed to qualify, then the Vice President elect shall act as President until a President shall have qualified; and the Congress may by law provide for the case wherein neither a President elect nor a Vice President elect shall have qualified, declaring who shall then act as President, or the manner in which one who is to act shall be selected, and such person shall act accordingly until a President or Vice President shall have qualified.

You may wonder: Why not do that now? Why not find that Trump engaged in insurrection and offer Congress the chance to remove the disability? I see two possible issues: First, if Trump is elected, the Congress seated in 2025 might elect to remove the disability. Second, the Supreme Court would be giving Congress a quick deadline because if they don’t move quickly, Trump will be kept off ballots. The Supreme Court giving deadlines is problematic because of the separation of powers.

The Amicus Brief filed by elections lawyers, including Hassan, basically argue that deciding after the election will create a political nightmare Trump wins. From the brief:

-

- If Trump wins an electoral-vote majority, it is a virtual certainty that some Members of Congress will assert his disqualification under Section 3. That prospect alone will fan the flames of public conflict.

- But even worse for the political stability of the Nation is the prospect that Congress may actually vote in favor of his disqualification after he has apparently won election in the Electoral College. Neither Mr. Trump nor his supporters, whose votes effectively will have been discarded as void, are likely to take such a declaration lying down.

I am not sure that ‘Keep him off the ballot to prevent a political nightmare if he wins’ is a compelling argument. After all, that was the procedure followed after the Civil War.

Note: If the Supreme Court adopts the procedure I laid out, the Supreme Court will not have to decide whether or not Trump engaged in an insurrection. The Court will also not have to decide whether Trump is an officer under Section 3. The Court doesn’t even have to define “insurrection” (the Court is not supposed to decide any more than it has to, and anything it doesn’t need to decide is considered dicta).

I’ll add this: If Trump is disqualified, and if his vice president assumes office, Trump will be the puppeteer and the vice president will be the puppet. And yes, the puppeteer can pull strings from a Georgia prison. In fact, pulling strings from a Georgia prison will thrill his supporters.

It seems to me that if Trump can win the election given everything we know about him — including court findings that he engaged in fraud in New York and that he sexually assaulted E. Jean Carroll–we have a problem that Section 3 of the 14th Amendment cannot solve.

Why people think this is an easy issue 🆕

Trump’s legal team has raised a number of weak arguments. As I said, it is not uncommon for a brief to raise 9 weak arguments and 1 strong one. If the strong argument wins, the weak arguments will be ignored. Lawyers call this arguing in the alternative: “The court should conclude A. If the court doesn’t conclude A, the court should conclude B.”

This is also called the kitchen sink method of arguing: Throw in everything, including the kitchen sink, because you never know what will work.

Pundits and lawyers spent time poking fun at Trump’s stupid arguments, giving many people the impression that all of Trump’s arguments were stupid. Other pundits told their audiences (essentially) that it’s an easy issue: Trump needs to be kept off the ballot because the Constitution says so (even though the provision isn’t about ballots, it’s about holding office. In other words, it isn’t about running for office. It’s holding office, and when a disability can be removed, there is a difference.)

Oral Arguments 🆕

Oral arguments were held on February 8. A transcript is here.

New arguments are not presented at oral arguments. What happens at oral arguments is that the justices ask questions. Therefore, we get clues about what they are thinking and which way they are leaning. You can often tell which justices are skeptical about which arguments.

This makes it a bit easier to predict what the Court might do. So, after oral arguments, commentators will have a better idea of which way the Court is leaning.

Here are a few highlights.

First up, Mitchell representing Trump.

Roberts asks a question about whether Section 3 limits access to the ballot:

Mitchell said:

Roberts points out that getting 2/3 is unlikely. Mitchell says the secretary of state shouldn’t predict the likelihood of a waiver.

Barrett (and Kagen) come to this question:

if we accept your position that disqualifying someone from the ballot is adding a qualification, really, your position is that Congress can’t enact a statute that would allow Colorado to do what it’s done either because then Congress would be adding a qualification, which it can’t do either. (17)

(In other words, if the states can’t disqualify someone, why should Congress be able to pass a law disqualifying someone?)

Mitchell says that the limit is on the states, not Congress.

Alito then chimes and adds, “Because section 3 refers to the holding of office, not running for office.” (18)

Mitchell raises the possibility that a “different factual record could be developed in some of the litigation that occurs in other states.” (Different documents can be admitted, different witnesses brought in. Some states, for example, might conclude that parts of the Congressional report were inadmissible hearsay.) (21)

Pages 24-28: Sotomayor and Mitchell are talking about why a third term is different. Answer from Mitchell: It’s not defeasable by Congress. (24) (In other words, Congress can’t undo it.) Sotomayor ends up saying, “Ok now I understand.”

Page 33-35: Alito and Mitchell agree that we have two separate issues (1) Did the person engage in insurrection or rebellion and (2) is there are reasons Congress should lift the disability.

Page 36 – 52. They move on to the “officer” question. Mitchell sort of concedes this isn’t his strongest argument.

From Barrett: Would removal from office under section 3 be at odds with impeachment / removal? (57) Mitchell: There is nothing that says impeachment is the only way to remove.

Barrett asks whether due process was followed (59)

Mitchell says, “The proceedings below were highly irregular . . . but we didn’t spend time on that because winning on due process would leave the door open for a do-over in Colorado.” (60)

Jackson: “So, if we agree with you on that, what happens next? I mean, I thought you also wanted us to end the litigation. So is there a possibility that this case continues in federal court if that’s our conclusion?” (63)

Mitchell then says only with legislation. (weak answer)

Next up, Murray for Colorado.

Thomas gets to the ballot issue right away:

Do you have contemporaneous examples — and by contemporaneous, I mean shortly after the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment — where the states disqualified national candidates, not its own candidates, but national candidates? (67)

Murray’s answer (basically): No, but that’s not surprising.

Roberts:

I’d like to sort of look at Justice Thomas’s question sort of from the 30,000-foot level. I mean, the whole point of the Fourteenth Amendment was to restrict state power, right? States shall not abridge privilege or immunity, they won’t deprive people of property without due process, they won’t deny equal protection. And on the other hand, it augmented federal power . . . (this is a good point and one I didn’t think of.) (71)

Murray: we located the states’ power in Article II, not the 14th Amendment.

Roberts pushes and asks if he has a way to rely Section 3 for that?” (71)

Kavanauh and Kagan both jump in to explain the problems: You can’t use the elections clause to explain the 14th Amendment. (The Amendment amends the Constitution. He is using the lesser to explain the greater.)

Kavanagh then wants to define “insurrection” and wants to know who decides the question. (74)

Kagan then says this (really hammers him):

But maybe put most boldly, I think that the question that you have to confront is why a single state should decide who gets to be president of the United States. In other words, you know, this question of whether a former president is disqualified for insurrection to be president again, you know, just say it, it sounds awfully national to me. So whatever means there are to enforce it would suggest that they have to be federal, national means. Why does — you know, if you weren’t from Colorado and you were from Wisconsin or you were from Michigan and it really — you know, what the Michigan secretary of state did is going to make the difference between, you know, whether Candidate A is elected or Candidate B is elected, I mean, that seems quite extraordinary, doesn’t it? (74-75)

Kagan: “Why should a single state have the ability to make this determination not only for their own citizens but for the rest of the nation? (76)

Murray: No, because this Court will decide.

This is something he keeps doing: He keeps saying, “This Court needs to decide that what happened was an insurrectin and that Trump engaged in one” (which was what the headlines were all blaring before oral arguments. The Supreme Court needs to decide!)

Kagan raises the question of how the Supreme Court would review the factual findings. (Murray never answers this.)

Gorusch stresses that section 3 is about holding office, not running for office. (81)

Murray: “The fact that Congress has an extraordinary removal power does not negate that the disability exists today and exists indefinitely into the future.” (83)

Sotomayer seems to agree with Murray on this. (83)

Roberts repeats the problem of a handful of states deciding who can be president. (84) (Murray repeats that the Supreme Court should decide now.)

This next exchange isn’t good for Murray:

Alito:

(paraphrase): Suppose that the outcome of an election for president comes down to the vote of a single state but the legislature sees the polls and knows the candidate they want will lose. Can they pass legislation like candidate A, thinks candidate A is an insurrectionists and order the electors to vote for someone else? Do you think a state has that power?

Murray: “I think they probably would . . . ” (90)

(See the problem? Murray has just said that a partisan state legislature can decide the president election by ignoring the will of the voters in the state. Isn’t that what Trump wanted to do in 2020?)

Jackson, going back to Kagan’s question, wants clarification on what happens if different states come to different conclusions about whether a person is disqualified.

Murray, “Well, certainly if Congress is concerned about uniformity, they can provide for legislation and they can preempt state legislation.”

Jackson: You just told us that wasn’t necessary . . . (his position is that the statute is self-executing) why would the framers create something that would create “interim disuniformity.” (96)

Murray: They were concerned with keeping insurrectionists out of office. (Weak) then, basically, this court decides.

Alito: (paraphrasing) that would turn us into a fact-finding court. (98).

For the next few pages, Murray stumbles. He doesn’t really have a good answer. (I think because there isn’t one.) Sotomayor comes in and tries to get him to answer the question . (102)

Kagan comes back and hammers the point about why one state should get to decide for everyone. (105-106)

Also, toward the end, Kagan asks this:

If we think that the states can’t enforce this provision for whatever reason in this context, in the presidential context, what happens next in this case? I mean, are — is it done?

Murray:

If this Court concludes that Colorado did not have the authority to exclude President Trump from the presidential ballot on procedural grounds, I think — I think this case would be done, but I think it could come back with a vengeance because ultimately members of Congress would — may have to make the determination after a presidential election . . .

Jackson:

And there is no federal litigation, you would say?

Murray: Well, that’s correct, because there is no federal procedure for deciding these issues, short of a criminal prosecution.

Next up, Stevens for Griswold (Colorado Secretary of State)

(This mostly repeats)

After you read the transcript, re-read the questions Stephanie Jones asked Larry Tribe on Twitter in December. Tribe never answered.

Now he wants to change the subject:

Former Judge Luttig, who, like Laurence Tribe, insisted for months that the Constitution was clear: Trump must be kept off the Colorado ballot, responded to the oral arguments by saying that what the Supreme Court was obviously about to do was a clear error.

Judge Luttig’s failure was failing to anticipate what the Supreme Court might do. He was so sure he was right he could not see other possible outcomes. He failed to see the weakeness in the position he was advocating.

There is nothing wrong with this. Lawyers make mistakes all the time. The problem is that lots of his followers on social media mistook his legal opinion for a fact, perhaps because he mistook his own legal opinion for a fact.

The second-to-last paragraph in your post says, “ Judge Luttig’s failure was failing to anticipate what the Supreme Court might do. He was so sure he was right he could see other possible outcomes. He failed to see the weakeness in the position he was advocating.”

I think that you may have left out a “not.” That is, “ He was so sure he was right he could not see other possible outcomes.”

Here is the issue I still do not understand. If in fact the SC defines an insurrection, which you’ve argued they should (so I am assuming here they can). What is the problem with using the Colorado definition narrowly defined (or slightly modified as needed) to also set the precedent narrowly for use of this Amendment? From what I’ve read Colorado allowed Trump’s representatives to be heard and their Supreme Court reviewed lower court findings. How does that make the SC a trier of facts if they’re affirming a definition for the purposes of Amend 14, Art 3?

If that definition indeed applies to Trump can they not affirm it for the purposes of disqualifying a person from holding office? Saying it allows Colorado to decide for all states doesn’t make sense to me, if his conduct disqualifies by a SC definition, it qualifies not matter which state raises it. . It would be the SC upholding the Constitutional Amendment under a defined circumstance.

Could there not be a precedent that when the issue comes up with a candidate it should be petitioned through the courts and allow it to go to the SC for a final decision if needed (after they define it)? That way any state could petition under a narrowly defined definition, but the SC could either uphold or deny if the circumstances are ridiculous. They could declare he could run but not hold office unless Congress lifts the disability. Roberts said Congress removing the disability is unlikely, but that doesn’t seem like it should be a reason not to follow the Amendment.

At that point the SC could say this person can stay on the ballot but will not be eligible to hold office unless 2/3rds of Congress removes the disability. I don’t see people disqualifying left and right over everything if the definition is narrow enough. What am I missing here? It’s not ideal but neither is giving a person who clearly and factually attempted to overthrow an election another shot at it.

The argument the justices were making is that different states can have different procedures, allow in different evidence, have different witnesses, and different expert testimony so that, even with the same definition, the conclusions can be different.

The Supreme Court is not a finder of fact. They don’t weigh evidence. Someone else has to do that. One thing that occurred to me after I wrote that is that the Bill of Rights guarantees a jury trial in both civil and criminal matters. I think what they were hinting at was that there would have to be a trial in federal court, using federal rules of evidence (one standard for everyone).

It’s not clear what their final opinion will look like. But it seems pretty clear that they don’t think section 3 is an access-to-the-ballot requirement. It’s a “hold office” requirement.

Isn’t the Supreme Court a finder of fact in Original Jurisdiction cases? Why couldn’t this be considered a similar sort of case?

Original jurisdiction applies in certain circumstances and this isn’t one of them.

It’s in the Constitution:

“In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction.”

Everything else is appellate jurisdiction.

So all the legal experts calling for the Supreme Court to decide that Trump was ineligible forgot to read the Constitution.

Could one state bring suit against another on the grounds the the electors chosen by the other state are pledged to an ineligible candidate?

That could happen, but the quicker way would be what happened after the Civil War: A federal prosecutor brings the action in federal court.

Interesting discussion from the Heritage Foundation.

They hope for a decisive, dispositive result from the SCOTUS (preferably in Trump’s favour).

The worst result is to kick the can down the road, to be revisited after the election (of Trump).

They think the easiest (and most likely) escape route the SCOTUS will adopt is that the President is not an officer of (or under) the United States, and so the 14th(3) does not apply to Trump in any case.

Another novel argument is that 14(3) is no longer an “active” amendment, based on:- the unique circumstances of its creation, leaving its enforcement to Congress, and Congress’s subsequent amnesty legislation, in 1872, 1898 and its effective repeal in 1948.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h3UMKx4-ikM

9-0

And by implication there is no active legislation to stop Trump.

Will Congress try to pass something?

Slight Correction:

As the USSC (and I posting here previously) note:

The 1870 Enforcement Act has been repealed, and the “successor” act is 18 U. S. C. §2383, which provides for Federal criminal prosecution.

But of course, no-one has been prosecuted in relation to the events of January 6th under that Act !

How can Trump become the first?

Not a bad previous analysis from me as a Brit non-lawyer. The USSC seem to agree.

I wonder if they read your blog? (^_-)

The three partial-dissents claim that this all goes too far.

No doubt they realise that the very subtle, clever judgment of the majority puts to bed the question that Trump will ever be held to be an “insurrectionist” by any due process.

Did you read this blog post?

If you did, re-read the pinned series entitled “There are No Yankees here,” and pay particular attention to the response to the Gamble case. You are making the same mistake.

“I am not sure that ‘Keep him off the ballot to prevent a political nightmare if he wins’ is a compelling argument. After all, that was the procedure followed after the Civil War.”

How did the electorate respond when folks whom they elected were disqualified after the election?

IDK, but I know they didn’t start a 2nd civil war.

I suspect that in this day & age, were DJT disqualified after having won the election, the part of the electorate that voted for him absolutely would start a 2nd civil war. I mean, really. Look at their conduct in the wake of his having LOST the 2020 election. They’re certainly not going to be less rebellious than they were in 2020 if he wins & is disqualified & disallowed to become POTUS. Heck, even if he’s preemptively disallowed to become POTUS by denying him ballot access, they may mount a civil war or other type of rebellion.

Preventing the “political nightmare” of a civil war by not risking letting him win & not be seated seems pretty compelling to me.

Ask the Jacobins & Montagnards how they would deal with Trump. Odds are we won’t apply their method to rid ourselves of DJT, but disqualifying him before the election is about as near as we can get given that the Senate failed to politically emasculate him.

“The brief filed by the election lawyers is weak and problematic: Stop him now to avoid a political nightmare.”

Weak & problematic? Avoidance of a political nightmare is essentially the reason Section 3 was included in the 14th Amendment, or so it seems by reading the debate of the 39th Congress.

EG:

“[Section 3] is a measure of self-defense. It is designed to prevent a repetition of treason by these men, and being a permanent provision of the Constitution, it is intended to operate as a preventive of treason hereafter by holding out to the people of the United States that such will be the penalty of the offense if they dare commit it.”

– Sen. Waitman T. Willey. Full text of “Debates That Led To The Creation Of The Fourteenth Amendment”

(https://archive.org/stream/DebatesThatLedToTheCreationOfTheFourteenthAmendment/Debates%20that%20led%20to%20the%20creation%20of%20the%20Fourteenth%20Amendment_djvu.txt)

A judge or court should never make a ruling based on political considerations. This is what the Court did in Bush v. Gore and it was wrong and they know it was wrong. Sandra Day O’Connor later regretted a political decision.

The 14th Amendment was not intended to avoid a ‘political nightmare.’ Fortunately, we know exactly why it was enacted because it is all recorded. It was enacted to keep former Confederates from taking office. There is a historical record of the intentions.

(Also, as one of the justices pointed out, the 14th Amendment was specifically, by it’s own terms, intended to limit state power after the Civil War.

I struggle to see how Section 3 is a limit on states’ power, even though I see how the rest of the 14th is so.

Section 3 is, to my mind, like wine with dinner. Dinner is eaten to nourish the body & the wine is just along for the ride, its presence having nothing to do with nourishment & everything to do with food courses being a convenient reason to have wine. One needn’t have dinner to have wine, but since one’s having dinner, one may as well have wine too.

“A judge or court should never make a ruling based on political considerations. This is what the Court did in Bush v. Gore and it was wrong and they know it was wrong. Sandra Day O’Connor later regretted a political decision.”

Yes, Bush v. Gore was a wrongly chosen occasion to incorporate political considerations into the decision the Court gave.

I’m unsure that political considerations should never inform the Court’s decisions. If, for example, it takes including the political consideration that the decision may avert civil war, even if it doesn’t avert & may yield lesser degrees of violent unrest, I think the justices are obliged to incorporate political considerations into the making of their ruling.

They too took an oath to the US. They surely can’t sit in their stone tower & be, like, we’re gonna rule X despite the fact that we have reason to suspect that ruling X sets up the framework for sundering the US. Should we just buy them some fiddles to go with their “togas?”

The dispassion & legal purity of the interpretations the Court renders is often fitting, but not always.

The Court didn’t need to incorporate political considerations in Bush v. Gore – throngs of people weren’t suggesting they’d take up arms over the matter; nobody was, as now, talking about secession – but it did so. That it did when it wasn’t necessary, didn’t even seem was the error.

There is a time & place for everything. Knowing that is why I just cannot abide the notion that political considerations should never make rulings based on political considerations.

I find it strange that we need a definition of “insurrection.” Why can’t insurrection be a term like “pornography,” which Justice Potter Stewart noted he couldn’t define but knew it when he saw it?

That came from a Supreme Court justice. That’s my point. The Supreme Court decides. We don’t decide.

Okay. I see what you mean there, & yes, it’s their decision to make.

The Amars’ amicus brief gives interesting historical context to the specific wording of Section 3, namely the 1860 plot to prevent Lincoln’s inauguration, but I’m not sure it does anything more than affirm its relevance. https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/23/23-719/295994/20240118094034746_Trump%20v%20Anderson.pdf

I do find it a strong argument that, since S3 gives Congress the authority to lift the disqualification at any time, removing an oath-breaking insurrectionist from a ballot would be at the very least premature. As a political question, it’s logical and sensible for it to fall to voters, and then to Congress rather than the other branches. To me, that’s the easy part. I’m just not sure this Congress would be up to the burden if it does fall to them. Heck, I’m not even sure they’re up to counting the electoral votes.

Could well be 9-0 for Trump.

Who decides what is an “insurrection”, and your supposed guilt?

Your political opponents? The main-stream-media? The mob?

No criminal court has charged ANYONE, let alone Trump, with such a crime. The Senate has acquitted him (or failed to convict, if you want to be precious)

The 14th Amendment, Section 3 was conceived after the devastation of a bloody Civil War which lasted 4 years and cost at least 650,000 lives…

In comparison, the 6th January was a side-show that lasted a couple of hours. A “riot” of a few hundred hotheads, at worst, with Trump’s direct culpability sketchy, at best.

Before even considering the merits of any alleged unqualification/disqualification, it is clear the Constitution envisages – and provides for – an unqualified President-elect, [20th Amendment] or a disqualified President-elect [14th Amendment, Section 3, (assuming it applies at all to a President-elect)], who may either subsequently qualify, or be un-disqualified by Congress, respectively.

To circumvent these Constitution provisions by (a state) barring, ex-ante, a candidate [passing over any considerations of due process] is surely constitutionally impermissible (not to mention morally repugnant and politically incendiary, reducing American elections to not who can win most votes, but who can cancel most votes, before they’re even cast) ?

As all your posts (and other writings) I found this brilliant, informative, clear and evenhandedly stated.

I think the passion many have formed for Amend 14 Sec 3 is of a piece with various other attempts to define a single easy thing that will solve America’s current crisis quickly and without much inconvenience. You point out why that’s impossible with a single portion of a single sentence: “… inserting phrases in the Constitution designed to restrain would-be power-grabbers won’t actually restrain a power-grabber.” There will be ways found around every possible quick and easy fix, around every law, and around every court ruling. As you’ve also pointed out elsewhere, democracy will survive if, and only if, enough people want it and work to save it.

Much of what we are, what we want, and what we aspire to can’t be reduced to single sentences, laws, customs, or even rendered clearly in words. Learned Hand has the right of it. Nothing can be achieved unless the spirit to achieve it is present, and can defeat the always-present spirit to undermine it.

I was so sure I knew exactly how this should all turn out until I read this essay. I am now in a much healthier state of humility and devotion to the democratic process than I believed possible for me.

Thank you for this eloquent analysis.

I especially liked this one.

I bought a red hat that reads “Amendment XIV Section 3” to troll my MAGA friends. Unfortunately, most of them do not understand it. I knew that application of that section of law was not a magic bullet, for the reasons so artfully articulated above. I just wanted a little playful pushback against the cultish drives of my colleagues. And yes, I still associate with such people, because I haven’t given up on America.

It is also contended that the sole right to declare the existence of an insurrection (or invasion), and call on the militia for assistance is vested in the President.

“[T]he authority to decide whether [an] exigency [justifying the exercise of military power] has arisen, belongs exclusively to the President, and . . . his decision is conclusive upon all other persons.”

Martin v. Mott, 25 U.S. 19

Trump did not declare that an insurrection was occurring. Ergo, there was no insurrection.

from the text of the judgment:

“Is the President the sole and exclusive judge whether the exigency has arisen, or is it to be considered as an open question….? We are all of opinion, that the authority to decide whether the exigency has arisen, belongs exclusively to the President, and that his decision is conclusive upon all other persons. ”

Martin v. Mott, 25 U.S. 19 (1827)

The Twentieth Amendment, Section 3, also says: (inter alia)

“If a President shall not have been chosen before the time fixed for the beginning of his term, or if the President elect shall have failed to qualify, then the Vice President elect shall act as President until a President shall have qualified; and the Congress may by law provide for the case wherein neither a President elect nor a Vice President elect shall have qualified, declaring who shall then act as President, or the manner in which one who is to act shall be selected, and such person shall act accordingly until a President or Vice President shall have qualified.”

IANAL, but does not the above entertain the possibility, for example, that a 34/33/32/31 year-old on inauguration day could be lawfully elected, and not barred from standing, since the Constitution itself implicitly provides for such a possibility and its remedy?

“Until a President shall have qualified…” implies that an ostensibly disqualified President-elect who may subsequently qualify (e.g. by reaching the age of 35 during the term, or by having the “insurrectionist” disability lifted by Congress) cannot be barred ex-ante from standing, since that would render these clauses of the Constitution without meaning or purpose, which is impermissible.

It seems to chime with the 14th Amendment’s ability for Congress to overturn an insurrectionists’ disability to “hold the office”. Ability to hold the office – not to stand, or be elected.

Qualifications such as 35 years, natural born citizen, 14 years a resident are matters of fact, although they could, and have, been litigated to establish the facts.

Being labelled an “insurrectionist” is an accusation (of a statutory crime), which surely must be subject to due process, and cannot be determined by an election administrator or a local civil court (exclusively peopled by the accused’s political opponents).

The 14th Amendment also says (Section 5)

“The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.”

Could it not be argued:

a) Congress has indeed, by appropriate legislation, enforced the provisions: (18

U.S.C. § 2383) and the Enforcement Act 1870 (repealed in 1948)

b) to date, not one person – least of all Trump – has been charged, let alone convicted under any statute enacted by Congress that flows from the 14th Amendment.

Due Process?

Under its own powers, Congress impeached Trump for “incitement of insurrection”, and the history books record that he was acquitted. An intended second motion to bar him from future office thus fell by default. Res Judicata ?

[writing from the UK – no dog in the fight !]

You raise some very good points, except the last. Double jeopardy surely only applies to the proper judicial process. The impeachment acquittal by an entirely partisan panel cannot substitute for a jury trial. No member of the impeachment panel would have survived voire dire in a judicial trial.

I believe there are four possibilities:

a) jury conviction followed by impeachment

b) jury acquittal followed by impeachment

c) impeachment conviction followed by jury trial

d) impeachment acquittal followed by jury trial

While a),b) and c) seem to be settled (affirmative), I’m not sure d) is.

In 2000, the DOJ offered an opinion that d) was also affirmative, while acknowledging numerous doubts.

https://www.justice.gov/file/19386/download

Thanks for that reference. I like these quotes that point to an impeachment acquittal NOT being an impediment to a criminal trial:

* impeachment trials “ may sometimes be influenced by political passions and interests that would be rigorously excluded from a criminal trial.”

* an acquittal by the Senate will often rest on a determination by at least a third of the Senate that the conduct alleged, though proven, does not amount to a high crime or misdemeanor. Such a judgment in no way reflects a determination that the conduct is not criminal in the ordinary sense.

* if the scope of the Impeachment Judgment Clause were restricted to convicted parties, “ the failure of the House to vote an impeachment, or the failure of the impeachment in the Senate, would confer upon the civil officer accused complete and — were the statute of limitations permitted to run — permanent immunity from criminal prosecution however plain his guilt.”

Once again, heartbreaking truth. Thank you Teri.

I would natvely expect that “what does insurrection and rebellion mean” is a question of law and appropriate for the Supreme Court to answer. If so, and say if they developed a test for that, would they send the car back to have the test applied by the lower court, or apply it themselves to the evidence previously presented?

The CO court covered what constitutes an insurrection. If the Supremes don’t come up with something different, then it has, at least tacitly, accepted CO’s reasoning.

I always appreciate a well-reasoned expression on a subject that is fraught with emotional baggage. As I read this, the one thought that kept creeping in was: Damn (as in to damn) Schrodinger concurrent with Damn (as in the expletive) Schrodinger. It is so easy to agree with those who espouse our own feelings on a subject. With those with whom we disagree… not so easy. We need to hear from people who are not taking sides. For that, I thank you.

Section 5 says “The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” How does that bear on the answer: If he runs and wins, the Congress can boot him out?

The law would have to be in place first. Laws generally can’t be retroactive.

It is inconceivable to believe that our Constitution’s founders and the14th amendment’s framers goal was to allow a tyrant in the former and an insurrectionist in the later.

Should an insurrectionist be allowed to be on the ballot for an office that they are constitutionally barred from serving, only if the disqualification is lifted by a 2/3 Congressional vote?

But what if the vote falls short? Then what?

Hi, Paul: I think you missed the chronology. Remember, I am making no predictions about what the Supreme Court will do, but suppose the Court keeps Trump on the ballot. Heres is one worst case scenario:

(1) Trump wins the election

(2) By some procedure that we don’t know yet, Trump is determined to be an insurrectionist under the definition in section 3 (which we also don’t know yet)

(3) 2/3 of both Houses refuse to lift the disability

(4) Trump becomes president.

Here is another:

(1) Trump wins the election

(2) By some procedure that we don’t know yet, Trump is determined NOT be an insurrectionist under the definition in section 3 (which we also don’t know yet)

(3) Trump becomes president.

It’s also possible, if the Supreme Court keeps Trump on the ballot, that he will lose the election.

I quoted James Madison, who was one of the Founders and influential in writing the Constitution. Please go back and read more carefully what he said about parchment barriers (you might want to click through and read the entire Federalist Paper #48.)

Democracy always contains a self-destruct button. At any time, the voters can elect a candidate who promises to demolish democratic institutions. Because of the institutions created by the Constitution, we were able to survive one term of Trump as president.

If enough Americans, in 2024, choose to vote for Trump resulting in Trump winning the electoral college, then we will have to conclude that enough voters have decided that they no longer want democracy.

If you want to know how to prevent this from happening, go to the menu, click on the “resources” page, and then start reading the “to do” list.

I recognize the ultimate importance of the voting booth, however our recent history shows how easy it can be to dupe voters. The quote used from Learned Hand was also very powerful. But I can’t help but wonder. Could the Supreme Court’s ruling include keeping Trump on the ballot, provide the definition of an insurrection ( I realize this is tricky, maybe they could conjure up Learned Hand) and affirm the requirement of a 2/3 approval vote of both Houses of Congress to seat a candidate? If so, would this add even greater weight to the outcome of the Jan 6 trial?

Also there have been many ‘hints’ recently from Jack Smith’s court filings to suggest that evidence will be forthcoming supporting the serious allegations that Trump is facing. This would appear to favor the prosecution case and could weigh heavily in the court of pubic opinion.

My day is made better every time a new post from you appears, many thanks Teri

“The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right”

I have never trusted groups of people who agree on everything. Especially if they smile.

That’s yet another reason why I know I can trust you.

The Jones tweet links to a Lawrence Tribe tweet says the arguments against using the 14th amendment provision makes it a dead letter – because it can only be used when it’s unnecessary. Seems to me that covers it. It’s a provision that can’t be used. There’s other stuff, like the emoluments clause, that turn out to be toothless as well. We know the best way to defeat Trump is at the ballot box – although last time that nearly didn’t work, this time he has fewer ways to weaponize the government when he loses. So we need to do it again.

I just can’t see how a person can be allowed to run for office in an election when he clearly has no intent of abiding by the result of the election, and has no respect for any election or election result. Isn’t this like including someone in your relay team who has demonstrated and declared his intent to take the baton and sit down on the track?

Here is how I always explain it: Democracy contains a self-destruct button. At any time, the people can choose leaders who promise to end democracy.

You can’t pass a law that will solve the problem. That’s what Learned Hand explained.

Yes. And probably what Benjamin Franklin meant when he reportedly said regarding having a Republic – if we can keep it.

I always felt that Trumps actions to try to bribe or implore Secretaries of State to “find” more votes, or hire fake electors, and those types of activities performed by henchmen were more likely to be viewed as a sign of trumps criminality, than the 1/6 riots.

After all, that’s what sealed Nixon’s fate, his knowledge and complicity with the hands on crooks. As a mob boss, trumps talent is getting others to do your dirty work and take the blame for it. That’s also why he is going to get away with it.

So, it’s up to the voters, whom I don’t entirely trust, to get rid of this crook.

Thanks for the food for thought.

Thank you, Teri, for your article, Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Spirit of Liberty. It is he most intelligent analysis of the matter I have yet seen. I look forward to reading more of your papers – it will help me understand the developments of this and other Trump cases.

Is it possible that the 14th amendment is poorly written, or at the very least incomplete? Terri, your statement “a decent argument can be made that the 14th Amendment, by its very terms, cannot bar someone from running for office and therefore, cannot keep a person off the ballot” while at the same time barring someone from holding office yields (as Anne points out at 3:13pm) a dire result that makes no sense. It does seem me you have honed in on a key question: who determines when someone has engaged in “insurrection or rebellion.”

I think this is certainly true. The Fourteenth Amendment was passed before the Confederates returned to Congress, so basically the northerners could do what they wanted. That Amendment was designed really to keep the elected officials who left to fight the war from returning. Then, not long after, Congress passed the Amnesty Act forgiving the former Confederates. You almost wonder why they didn’t just try to repeal section 3. (Likely answer: Passing a statute is a lot easier than Amending the Constitution.) It’s also clear they were thinking about another Civil War. It is unlikely that anyone at the time imagined a scenario where a sitting president incited an attack on the Capitol to keep himself in power.

The answer is in the 14th Amendment!

It is Congress that makes a determination of RESTORING an ineligible party via a 2/3rds majority, NOT the Supreme Court!

Neither Colorado nor Maine, or ANY other state, that removes trump from their ballot need put him back unless that prerequisite is met.

That is what the 14th Amendment says.

Basically my concern: “Given that section 3 allows for the removal of the disability, it is not clear to me that Section 3 applies to who can run for office. It applies to who can hold office. ”

Does this become the next “find the votes” move by Trump? It would make the fake electors scheme look mild.

It is necessary to consider that Congress elected to amend the Constitution rather than simply enact a statute. This is missing from all I have read. Congress was not only concerned with an insurrection – which the mob was guilty of – but with an insurrection against the Constitution – which the mob could not have been guilty of. The question becomes At what point did Trump bring the 14th Amendment into play? That is not a trivial question as is evidenced by the conclusion of the January 6 Committee that the citizenry is uninformed and in active.

The pair of paragraphs beginning “But they can’t both be right” puzzle me. Even for a federal office, isn’t the administration of elections a matter of state-level law and state-level action and adjudication? If so, individual states could perfectly well have their own idiosyncratic rules, definitions, and interpretations; and so long as those don’t conflict with Constitutionally grounded standards and statutory law, it seems to me to be a matter for the individual states. If so, there is an unwarranted leap in your logic—it would be neat and probably more equitable to have the same rules in all states but in our system I don’t see what compels this outcome. No one who remembers voting rights maneuvering in e.g. the Deep South can regard this conclusion with equanimity but in the absence of Constitutional proscription or federal legislation, I don’t see how to escape the conclusion. What am I missing?

States can have their own laws. The Constitution must be interpreted uniformly across the states. If a person is not eligible for office under the 14th Amendment, that would be nationwide.

I am not a lawyer, I am an engineer who has built cognitive systems. Daniel’s point is valid; systems with cognitive diversity are very robust to perception biases. The states (agents) independently determine the electors they sent to Congress, right? So let them. Embrace the diversity of approaches that States use to select electors. If they want to disqualify candidates under Article 14, Section 3 let them. Picking a President is a hiring decision, not a divine process. No one has a right to be president, or a right to vote for an ineligible candidate. Normal candidates will sail through without conflict, but compromised candidates like Trump will run into difficulties. These difficulties will create confusion and chaos, which is actually good. In distributed cognition systems (like the United States), the best solutions evolve slowly through a prolonged period of resolving chaos. Resolving the issues prematurely, as the SCOTUS may attempt to do, may feel better, but it rarely results in an optimal or even acceptable result. Bush vs Gore is a perfect example. By the time the States select their electors the issues will be out in the open, the electors sworn to the defective candidate diminished in number, and the decision making body (the VP, Senate, and electors) small enough to come to a consensus that we can all live with.

When I say “can’t” I mean legally.

We don’t get to invent whatever we want based on what makes sense. We have to follow the Constitution and laws of the land.

It works like this: The Constitution is the supreme law of the land. It must be applied uniformly in all states. States have their own laws, which can stand as long as they do not violate the Constitution.

Ever since Marbury v. Madison, the Supreme Court has had the task of deciding when state or federal laws run afoul of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court’s task is to make sure that section 3 of the 14th Amendment is properly applied. Because of the complexity of the issue, and the tangle of state and federal laws (and because this is a case of first impression) it is not possible to predict what the Supreme Court will do. It is also difficult to say what the Supreme Court should do, given the legal parameters.

Thank you, Teri. I’ve read your blog posts for several months now and this one is my favorite. Keep being “unpopular”. I would equate this to “without bias”.

I would like to read more Learned Hand. Do you have suggestions?

I have long argued that keeping Trump off the ballot is foolish and does not solve the problem. Trump and MAGA throughout the country on both federal and State ballots, must be defeated at the ballot box by wide margins if we want their style of governance to go away. Only the voters can sweep Trump and MAGA into the dust bin of history and restore our democracy to its former greatness. Only the vote has a chance to defeat this burgeoning authoritarianism.

But what do you do with a person who does not accept the results of an election? Trump had opportunities to challenge the results before they were certified, and claims that the institutions that certified the election are corrupted; he claimed and continues to claim that he is the victim of corrupt institutions. January 6, 2021 was an attempt to violently disrupt our institutions, and the participants in those events felt they had the right to do so because the institutions were corrupt.

Trump will not accept any result unless he is victorious.

I love reading Teri Kanefield’s posts because she analyzes the legal process, and concludes that she doesn’t know what the Supreme Court should do in this case. The case they will consider is not as simple as we’d like it to be, nor, as Trump and his lawyer state in public require his three very good appointees to “step up.”

I often wish not to post a public comment here, but to make a private one that you may well not care to read. After all, you seem more-than-adequately busy.