A political scientist said this after Thursday’s January 6 Congressional Hearing:

To be fair, she is not a lawyer and has no experience with criminal trials. I quote her because she has a large audience and she is influential, and because lots of people are saying similar things (including people who are trained in the law and should know better).

It’s much easier to prove something in the media because much of the evidence you see in the hearings and in the media would not be admissible in a criminal court.

The heightened standards in criminal court are because more is at stake. In a criminal trial, a defendant stands to lose constitutional rights such as liberty, property, and (in capital cases) life. So evidence has to meet certain standards, and not all evidence is admissible.

In a congressional hearing, the only harm a person faces is the truth coming out. Keeping the truth from the public is not a constitutionally protected right (even though Trump and the Congressional Republicans often act as if it is.)

Anonymous Sources

Much of the “evidence” you see on the news or read in newspapers would not be admissible in a criminal court.

One reason is because of anonymous sources. Major media can report “facts” after talking to anonymous sources. If the reporter is good and knows how to evaluate sources, the information is true and accurate.

But it can’t come into a criminal court as evidence because anonymous sources are hearsay.

Hearsay

At the hearing, Liz Cheney said,

You will hear testimony that the President didn’t really want to put anything out calling off the riot or asking his supporters to leave. You will hear that President Trump was yelling, and was really angry at advisors who told him he needed to be doing something more. And, aware of the rioters’ chants to “hang Mike Pence,” the President responded with this sentiment: ‘maybe our supporters have the right idea,” and Mike Pence “deserves it.”

Liz Cheney telling us what witnesses will say is double hearsay. In a criminal trial, the witnesses who heard Trump make such utterances must offer testimony under oath and withstand cross-examination. The defense will then try its best to discredit the witness, perhaps by showing that the witness has a history of lying, or a history of acting in his or her own best interests at the expense of the truth, or that the witness has an ulterior motive.

One problem with getting to Trump’s state of mind is that the evidence has to come from people in his inner circle, and many of them have a history of lying (or at least tolerating lies) because (to state the obvious) they are members of Trump’s inner circle.

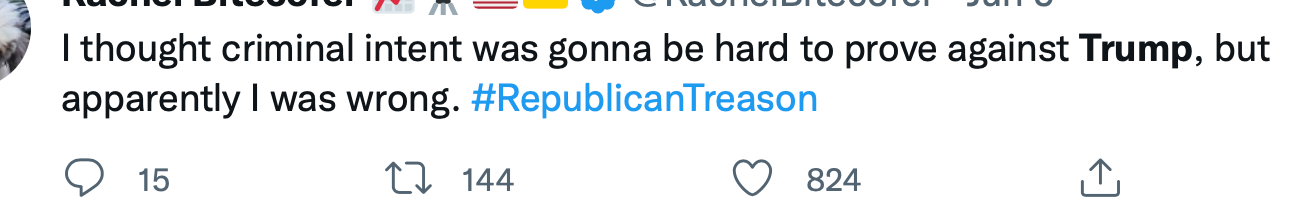

I’ve compared bringing down Trump to bringing down a mafia don or a gangster. If the people around Trump are willing to shield him, it gets difficult to get to him. This is explained in the Godfather, in this passage:

The Godfather gave orders to commit a crime in private to his Consigliere without witnesses, who then gave orders to another person without witnesses, who gave orders to the guy who commits the crime. To pin the crime on the Don, the Consigliere would have to turn traitor.

If the Consigliere does turn traitor, the defense then goes to work trying to discredit him (which may not be hard because, c’mon, the guy is a gangster).

Because of the standard of proof — beyond a reasonable doubt—all the defense has to do is raise a doubt in the minds of the jurors.

A thing can be true and provable in court without rising to the level of “proof beyond a reasonable doubt.”

This is why OJ Simpson could be acquitted in a criminal court, where the standards of proof are high, but held legally responsible for the murders in a civil court, where the standards of proof are lower.

Selectively Edited Videos

I’ve seen lots of clips from Trump’s January 6 speech in the Ellipse Park just before the insurrection. It’s hard not to watch those clips and the clips of the insurrection that followed and not be stirred to deep anger.

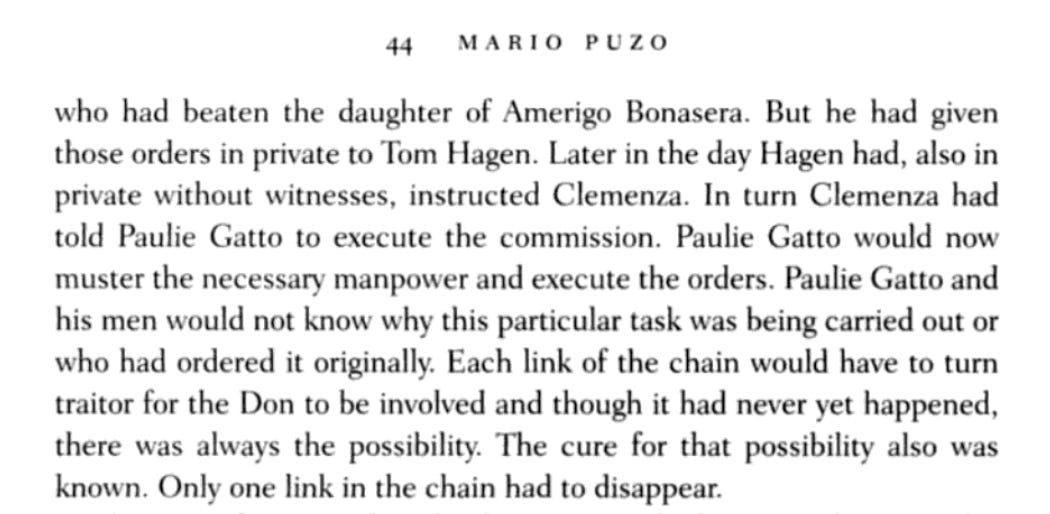

But we’re talking about evidence admissible in court, and I’ve never seen any clips run on TV that include this line from his speech:

I know Trump didn’t mean “peaceful” and you know he didn’t mean “peaceful,” but if the prosecution leaves out that detail, it could discredit the entire prosecution. The prosecution must confront the fact that Trump said, “be peaceful” and his defense will be, “I said ‘be peaceful’.”

We learned another interesting detail Thursday: The most violent and heavily armed of the militia groups that attacked the Capitol skipped the speeches on the Eclipse and went directly to the Capitol. See how that detail lends credence to the argument that Trump’s speech on the Eclipse didn’t prompt the violence? These guys were already planning to attack before Trump made that speech.

This isn’t to say Trump is innocent. Of course, he is guilty AF — but proving it in criminal court is not as easy as it looks.

Aside: Did you see the musical Chicago? The defense lawyer tricked the prosecutor into presenting bad evidence to the jury. The defense lawyer then used the fact that the prosecutor presented bad evidence to discredit the prosecution and get an acquittal for a cold-blooded murderer. This was fiction, but trust me: A defense lawyer would love it if a prosecutor tried to present a selectively edited video to a jury.

The Prosecution Must Prove Each Element of a Crime Beyond A Reasonable Doubt

Each crime is broken into elements. Here are the elements of seditious conspiracy:

- To conspire to overthrow or destroy by force the government of the United States or to level war against them;

- To oppose by force the authority of the United States government; to prevent, hinder, or delay by force the execution of any law of the United States; or.

The key word is “force.” If, for example, Trump conspired to stop the counting of the votes by sending a rowdy mob to make a lot of noise outside the Capitol and persuade the Congressional Republicans into voting against the electors because they didn’t want their constituents mad at them—that wouldn’t be “force.”

Liz Cheney told us, “Trump intended to stop the counting of the votes by force.” I don’t doubt that what she says is true and backed up by the evidence she gathered and the witnesses she spoke to, but her statement would not be admissible in court as evidence.

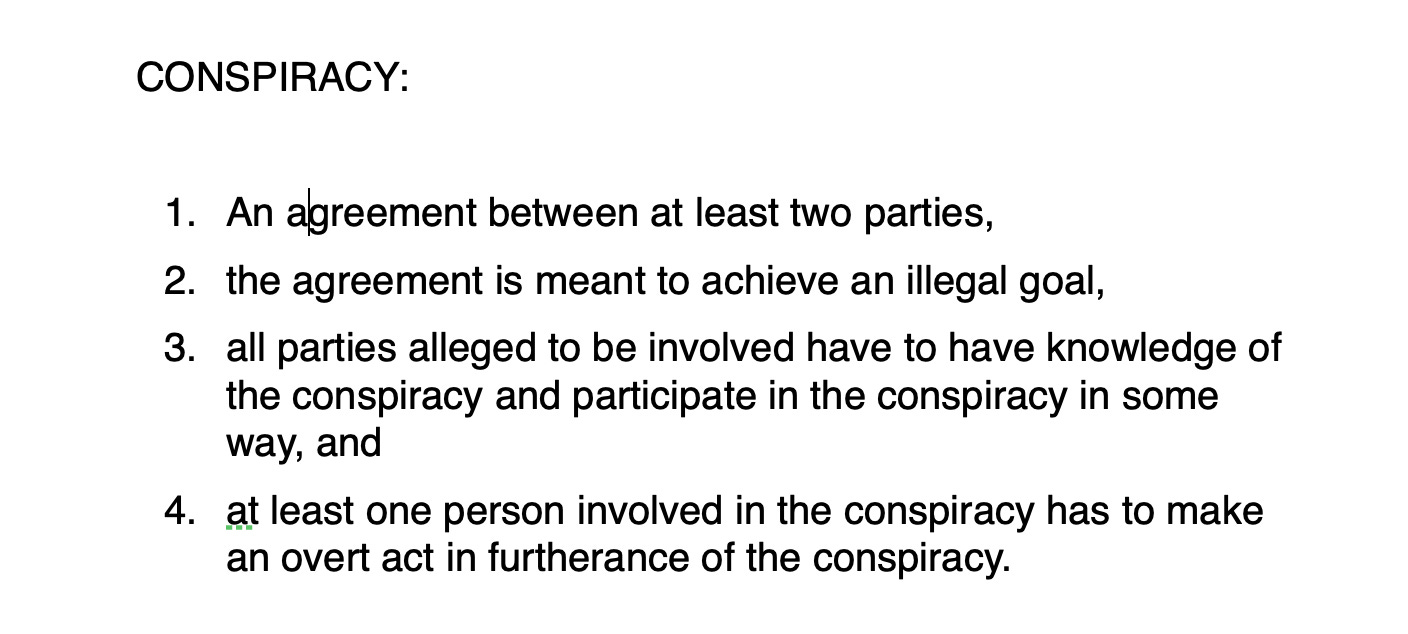

“Seditious conspiracy,” includes “conspiracy” which, in addition to proving the “intended force” element, also requires proving each of these elements beyond a reasonable doubt:

If the juror has a reasonable doubt about any one of these, the juror must acquit.

See how hard it is?

It’s meant to be hard. Our criminal justice system is based on the theory that it’s better to let 10 guilty people walk free than to wrongly convict an innocent person.

OJ Simpson was acquitted even though the prosecution had a mountain of evidence. What happened was that the defense systemically called into doubt each piece of evidence.

See: all the defense has to do is raise a reasonable doubt in the minds of the jurors and then the defendant gets acquitted.

If prosecutors are not careful, good evidence can be excluded from the trial and the jury never sees it

We have a thing called the exclusionary rule. Any evidence gathered in violation of a defendant’s constitutional rights is not admissible in court.

That’s why the gathering of evidence has to be done carefully in accordance with rules and procedures.

Rules and procedures slow things down.

“But, Teri: If It’s This Hard, How Does Anyone Get Convicted?

Federal prosecutors have better than a 95% conviction rate.

That’s because they know how to assemble evidence that meets the requirements of admission in a criminal trial. They anticipate defenses.

They don’t rush to trial because everyone on social media knows the person is guilty or because someone influential said so.

Sometimes a Person can be Guilty but get Acquitted

Sometimes juries get it wrong.

Sometimes good evidence is excluded.

Sometimes courts screw up.

That’s why it is important that we separate the function of the Congressional Committee from the function of a Criminal Court.

The goal of the J6 committee is to put the truth in front of the American people.

The goal of a criminal trial is to see if prosecutors are able to persuade a jury that they have collected evidence to prove each element of a crime beyond a reasonable doubt.

And that, my dearies, is why it’s easier to prove that something is reprehensible and morally wrong than it is to prove a person’s guilt in a criminal court.