This post draws from this Op-Ed I wrote a few days ago for NBC and a fourteen-minute video (I’ll add the link here shortly.)

Last week Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, said that it’s “highly unlikely” that he would allow President Joe Biden to fill a Supreme Court vacancy in 2024 if he becomes Senate majority leader—which of course would happen, of course, if the Republicans pick up seats during the midterm elections. He also said he may not even allow a hearing in 2023 if a seat became available then.

McConnell’s comments aren’t super surprising, which is part of the problem. If you recall, in 2016, when Supreme Court Justice Scalia’s seat became available, McConnell, who then the majority leader, took the unprecedented step of saying he would prevent President Barack Obama from filling the seat.

The Constitution provides that the president “shall nominate and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint … judges of the Supreme Court.”

In legal language, “shall” is forceful. It’s an imperative in the sense that nobody else can do it. We know from documents left by the drafters of the Constitution, that the Senate offers advice and gives consent to the president’s pick as a check to make sure the president doesn’t go off his rails and with autocratic motivations, appoint completely inappropriate justices.

The idea was that two branches of government would weigh in on the decision, but the president nominates and appoints justices.

McConnell saw a way to exploit this provision by grabbing power for himself that the Constitution didn’t actually confer: The power to say, “No, this president can’t appoint Supreme Court justices. I have the power to stop him.”

In fact, Scalia’s seat wasn’t filled until after Donald Trump became president. Essentially, the Republican stole a Supreme Court seat. McConnell has bragged that refusing to fill Scalia’s seat was “the single most consequential thing” he did as Senate majority leader. Now, five years later, McConnell said that is announcing ahead of time that if the Republicans gain a majority, he would do the same thing.

I want to talk about how effectively and efficiently a comment like this can destroy a democracy.

Legal scholar Mark Tushnet describes McConnel’s power grab as “constitutional hardball.”

Constitutional hardball is behavior that isn’t technically forbidden by the Constitution but subverts the intention of the Constitution. Constitutional hardball is played by those trying to permanently rig the game in their favor—which obviously destroys democracy. Constitutional hardball by its very nature batters and damages democratic institutions.

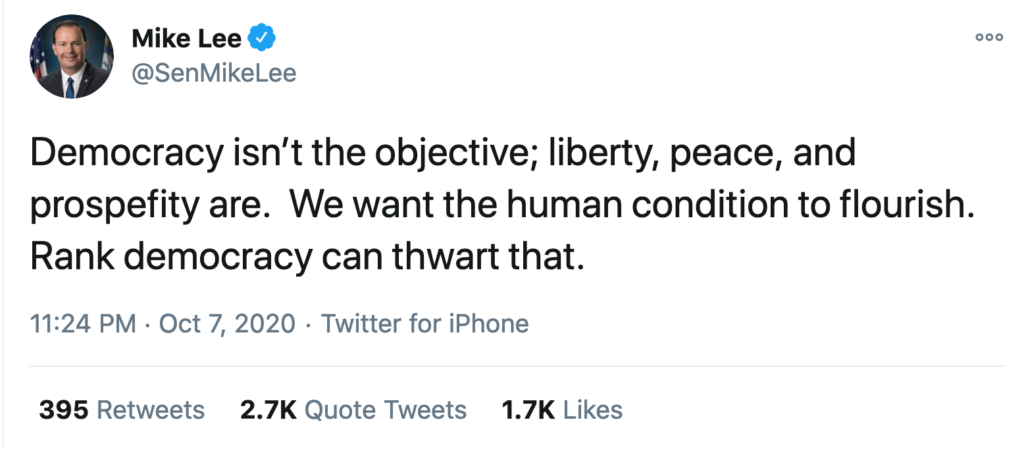

It’s easy to see why the Republican leadership wants to permanently stack the game in its favor. The Republican Party is having trouble winning national elections, because, for one thing, their numbers are shrinking. The Republican base is largely white and increasingly catering to white supremacists, but the country is growing more diverse. In a moment of rare honesty, a Republican senator, Mike Lee of Utah, said:

In other words, the Republicans would benefit from destroying democracy because if all of our democratic institutions work, they’re going to lose. So they look for ways to undermine democracy.

The Republican Party has also benefitted politically from politicizing the Supreme Court. The promise of appointing conservative justices gets their base to the polls. All of this started, by the way, because of the liberal Supreme Court from the 1950s and 1960s, that did things like end racial desegregation and enforce federal legislation giving rights to minorities. The conservatives have never forgiven that and have been on a 50 year campaign to stack the courts with conservative justices.

McConnell’s threat not to allow Biden to appoint Supreme Court justices will rally the base and thrill them and give them a reason to vote in the midterms.

You can see how McConnell found a wedge here. The intent was never for a Senate Majority Leader to able to say, “We’re not going to let this president appoint anyone.” The purpose of the “advice and consent” clause was to allow the Senate to veto a bad pick. But McConnell said, “what if I just don’t give my consent?”

The result is that instead of two branches of government weighing on the decision and working together, which was what the Constitution envisioned, one branch (actually, one person because the Republicans in the Senate do whatever McConnell says) can torpedo the process.

This renders government dysfunctional.

To quote Harvard Professor Steven Levitsky, co-author of How Democracies Die, the greatest danger to democracy is the government slipping into dysfunction, which will erode public confidence. When public confidence erodes, people become vulnerable to the appeal of a strongman, who promises to get things done.

McConnell’s threat (which we know he will carry through on) has a powerful effect. Once he says something like this, the opposition looks weak and ineffective because he has just gone outside the norms, or what we can call unspoken rules. What a neat trick, right? Say something outrageous, and by virtue of your outrageous statement, make your opposition look weak and ineffective.

It also riles up people who then demand that their leaders, in this case the Democrats, respond in kind.

This is the kind of response from people furious at McConnell. You see on social media:

This leads to what Levitsky and Ziblatt call “escalation,” which they say never ends well. When both sides engage in Constitutional hardball, democratic institutions will weaken more because the democratic institutions are being battered from both sides.

See how brilliant McConnell’s threat was? Simply uttering the threat undermines public confidence in democracy, which makes people vulnerable to a strongman who can do what the “weak” Democrats cannot do. It’s easy to rile people up and get them willing to overthrow democratic processes.

So what do we do?

A better, long-term solution is what legal scholar David Pozen calls anti-hardball reform that will depoliticize the Supreme Court and make it harder for McConnell to pull off a power grab.

Anti-hardball tactics “forestall or foreclose tit-for-tat cycles and lower the temperature of political disputes.” They do this by responding in ways that blunt power grabs without putting additional pressure and stress on the democratic institutions. They avoid escalation. Put another way, Pozen argues that anti-hardball tactics are “good government rules that both sides would adopt if they didn’t know the underlying partisan dispute.”

This isn’t to say that the response to comments like McConnell’s should be passive or mild. On the contrary, the public needs to understand that McConnell is engaging in democracy-undermining behavior.

I can pause here to point out another reason McConnell’s threat was brilliant (brilliant if your goal is to undermine democracy, so brilliant in an evil-genius sort of way). His brag and threat are hard to respond to in a soundbite. It’s easier to rile people than to educate them. It’s easier to destroy democracy than to preserve it. So the short-term problem is how to counter dangerous messaging.

A long-term solution is one that depoliticizes the Supreme Court so that, to use President Biden’s phrase, the Supreme Court can’t be used anymore as a political football.

Here’s an example of anti-hardball reform. Legal scholars Steven Calabresi and James Lindgren offer this idea: Congress passes legislation allowing for new Supreme Court appointments every two years and then transferring justices who have been on the court 18 years into some sort of senior or alternate status. This process of adding justices would stop when a particular number of justices has been reached. After that, replacing justices who have served for 18 years would continually renew the court.

Of course, this kind of legislation would have to be designed in a manner that comports with Article III’s good behavior clause. This is the clause that says federal judges hold their offices during good behavior. Basically this is the lifetime appointment clause. But there’s nothing to say that you can’t structure the court so they move into a different kind of position. The idea behind the good behavior clause is to give the justices job security so that they can do what they think is right without worrying about politics, or getting thrown off the court for their views. But a regulation like this treats all justices the same.

Dramatically increasing the number of justice would make it impossible for each judge to hear each case. Instead, cases would be heard by randomly selected panels, making partisan divides less overpowering. This would take away the “winner takes all” dynamic now (Meaning: there are more conservative justices, so the conservatives always win.)

To qualify as an anti-hardball tactic, additional justices of course would have to be appointed in a way that satisfies both the “good government” rule, for example, by creating nonpolitical or bipartisan selection committees.

Packing the court refers to putting in lots of justices on the court who are on your side. This is expanding the court in a non-partisan manner.

It’s obvious, given the behavior we’ve seen lately, that current Republican leadership wouldn’t go along with a good-governance plan because such a plan hurts them. They benefit from he politicizing the court. They benefit from battering these democratic institutions.

The Democrats are more likely to want something like this because they have been hurt by McConnell’s power grabs.

Biden has in fact appointed an independent commission of legal scholars, retired judges and practicing lawyers to research and recommend a plan to reform the courts. Biden himself said the court must cease to be a “political football.” So we can expect Democrats to get behind such a plan.

After all, McConnell already stole one Supreme Court seat and now he’s threatening to steal another.

Unfortunately, McConnell’s obstructionism, combined with the reluctance of some Democratic members of Congress to end or modify the filibuster, means a good-governance solution may have to wait until the Democrats build a larger majority or revise the filibuster, which of course would allow the Democrats, who now have a majority, to pass laws more easily.

We can also expect some Supreme Court justices not to like it. Why? Consider how much power Supreme Court justices have. One third of the government, the judicial branch, is divided 9 ways. Look how many ways the Legislative branch is divided. All those Senators and members of the House. The president has lot of power over 1/3 of the government, but for no more than 8 years. Justices can sit there for decades.

We have had 9 justices since 1869. According to the US Census bureau, the population then was under 39 million. Also according to the US Census Bureau, in 2021, the population was more than 331 million.

But we have the same number of justices. I don’t expect Supreme Court justices to willingly offer to dilute their own power. Nobody likes to give up power and importance. Well, some of them will probably be okay with it. I’d expect at least a few of them not to.

In the long run, Congress can either enact a good-governance solution depoliticizing the Supreme Court or risk our government’s slipping further into dysfunction.

Meanwhile, let’s have good government be the goal, not removing our gloves and descending to the level of Mitch McConnell. If neither party takes the high road, how will justice-minded voters know who to vote for?