This is a transcription of a video I recorded. I’m finding it easier to first record a video on a topic, and then edit the video. It turns out that talking for 9 minutes is easier than writing 3 pages. Who knew? (You can see the video here)

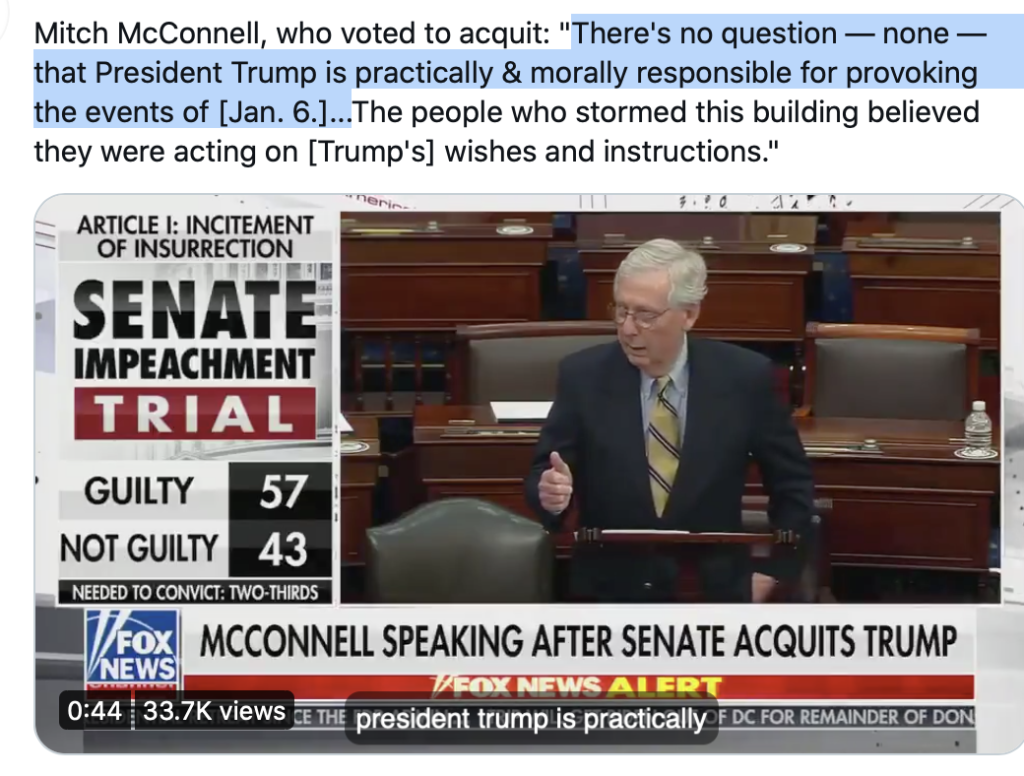

Remember after Trump’s second impeachment trial, Senator McConnell concluded that, “There’s no question — none — that Trump is practically and morally responsible for provoking the events of the day.”

McConnell went on to say that the courts, not the Senate were the proper venue for those seeking to hold Trump accountable–which was ridiculous. It was a way of punting responsibility and his own duties. It was also an avoidance tactic. It’s also wrong. The Senate was an appropriate place for holding Trump accountable.

But Courts are also an appropriate place, and lots of people (and prosecutors) are taking McConnell at his word. In fact, when two U.S. police officers, James Blassingame and Sidney Hemby sued Trump for damages for their injuries during the insurrection, they quoted McConnell in their court papers. They basically said that after listening to the evidence against Trump, McConnell concluded that Trump was responsible for the attacks and he sent us to the courts, so here we are.

Blassingame v. Trump is particularly bad for Trump for a number of reasons.

First, it’s a civil case, not a criminal case, and civil cases are easier to prove in court because there is a lower burden of proof for the plaintiffs. I talked about that in my last post. The prosecutor in a criminal case has to prove each element of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt. This is the highest possible standard because the defendant in a criminal trial stands to be punished by the government. A defendant in a criminal trial stands to lose his or her freedom. In capital cases, maybe even his or her life.

Civil cases, in contrast, are mostly about who pays for the damage. The law basically says that the person who causes the damage has to cover the cost of the damage. So in a case like this, we come to the same question as in criminal cases, but with a lower standard of proof. The question is: Did Trump cause the officer’s injuries? Put another way, if Trump had taken a different course of action—if he hadn’t insisted the election was stolen, and if he hadn’t riled up the crowd during the rally itself and the months leading up to the rally—would the officers have been injured?

Another reason this case is particularly bad for Trump: The defendants are police officers who sustained serious injuries. One weakness in a lot of tort cases (tort cases are injury cases) is that the plaintiffs don’t have actual damages, which means they don’t really have what’s called standing to sue. These officers did sustain serious injuries to their heads and backs. One continues to have back pain. They were sprayed in the face and body with chemical sprays. They were traumatized. Their lives were upended. In their court filing, these officers recount in harrowing detail how they were attacked with rocks, bottles, fire extinguishers, metal poles, pepper spray.

Yet another reason this is a particularly bad case for Trump: These are sympathetic plaintiffs. These officers are held up as heroes. One of the officers reported that all through the attack, insurrectionists hurled the “N” word at him.

This brings me to the next reason this case is particularly bad for Trump: Trump’s “defense” is usually based on cherry-picking the facts. His defenders say, “Trump told them to be peaceful.” Or “there’s nothing wrong with the word ‘fight.’ Cherry-picking facts sometimes works in the Court of Public Opinion, particularly in certain media outlets. But you can’t cherry pick the facts in court. The officers, in their court filing, laid out all the facts over a period of a few months, and the facts are devastating. The complaint filed by these police officers gives the history of how Trump riled his followers with lies, and how he knew that these “stop the steal” rallies were leading to actual violence. On January 6th he would have seen people in the crowds in military gear.

When a case like this is litigated, all these facts will be brought forward again. The most harrowing description of the attack comes from the viewpoint of the officers who were actually engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the insurrectionists.

In addition, the law in Washington D.C. is bad for Trump. Washington D.C. has a tort called “directing assault and battery.” Of course, Trump didn’t actually hit anyone. The question is whether there is joint liability. In other words, the question is whether Trump is also (and equally) responsible for the officer’s injuries.

One D.C. case says that for there to be joint liability, the words spoken by the defendant don’t have to be a literal call to action. He doesn’t have to say, “Storm the Capitol and hurt people.” It’s enough if the words and actions of the defendants “plant the seeds of action and are spoken by a person in an apparent position of authority.”

The case law also tells us that the defendant need only have foreseen an “appreciable risk of harm to others.” One case on point was about a security officer in a trailer park who urged a young driver to demonstrate how fast his car could go. While speeding around the park, the young driver lost control and caused an accident. The court held that the security officer was jointly liable even though, obviously, the security officer didn’t say, “drive fast and hurt someone.” It was obvious from “let’s see how fast your car can go in a trailer park” that it was foreseeable that someone could get hurt.

If you’re worried about how the plaintiffs are going to prove that Donald Trump could have (or should have) foreseen an “appreciable risk of harm to others,” don’t worry. Circumstantial evidence can be used to state of mind. Circumstantial evidence just means you look at the circumstances and you draw a conclusion about what a person could have known or should have known. If direct evidence of state of mind was required to prove intent, the only time you’d be able to convict someone for a crime would be if they confessed.

From these facts surrounding these circumstances on January 6 and leading up to January a jury can conclude that Trump knew or should have known that there was “appreciable risk” of harm.

And yes, “appreciable risk” is vague. One side will argue that there was an appreciable risk of harm. The other will argue that there wasn’t. In this case, I’d rather be on the side arguing that any dodo would know that if you tell this particular crowd under these circumstances to go “stop the steal” where the goal is to stop the voting, there is obviously an “appreciable risk” of some harm.

Another reason this case is bad for Trump: Discovery in civil cases is wide open. The civil court is trying to get to the truth. In a civil court, you don’t have a fifth amendment right to stay silent unless you have criminal vulnerability. Since this isn’t a criminal court, the jury can take your silence into account. If you say in a civil court “I refuse to testify because I have criminal liability in this matter,” it doesn’t make you look innocent and the jury can weigh that.

Because discovery is wide open, discovery in this case is likely to bring to light evidence that House Managers in the impeachment trial were not able to get their hands on. For example, remember the reporting from “close advisors” to Trump who said that Trump watched the TV coverage of the insurrection with interest, buoyed to see that his supporters were fighting so hard on his behalf? Imagine bringing these witnesses to the stand and having them testify under oath.

If a jury believes accounts that Trump was sort of thrilled to see the violence going on in the Capitol, it’s pretty much all over for Trump with these cases.

I’ll add that Washington D.C. is a terrible place for Trump to face a jury. I’m sure he’d much rather be in, say, Florida, where he might have at least a hope of getting a sympathetic jury, but he has no grounds to move the case. The harm occurred in D.C. If you go someplace and hold a rally, you automatically subject yourself to the laws and courts in that jurisdiction.

Trump tends not to do well in court, where facts matter. He does well in forums where facts don’t matter.

For this reason, Trump is likely to try settle this case to avoid a trial and discovery. It should be obvious to Trump and his lawyers, that if this case goes to trial, the possible outcomes for Trump range from bad to terrible.

I’ll be watching as this case develops, so check back for updates.