This post will build on last week’s post, where I laid out the facts as we know them and offered explainers on the law. If you missed it, start here.

The Theory of the Case

Good advocates organize their cases around a theme or focal point called the theory of the case. Because there are often so many details haphazardly presented to the jury, jurors need an overarching narrative or theory. A good theory of the case is easily graspable by the jury, is compelling, and accounts for all the uncontested (and easily proven) facts.

The theory of the case is basically a concise argument of why your side should prevail and informs all other decisions: Which witnesses to call, which evidence to present, and the focus of cross-examination.

Both the defense and the prosecution will present their theories of the case in opening arguments.

Litigation is About Competing Theories

Before law school, I earned a master’s in fiction writing and spent seven years teaching English at the college and university levels while writing and publishing fiction. Once in law school, I noticed the overlap between fiction writing and litigation. (No, not because lawyers, like fiction writers, make stuff up!) It’s because stories, like legal cases, have conflict, characters, and resolution. A good story, like any good metaphor, stands for something greater than itself. A compelling and important legal case also stands for something greater than itself.

My civil procedure professor told the class that litigation is storytelling. I came to understand that more specifically, litigation is competing versions of the same story. Two people can witness the same incident and come away with different views of what happened. Biases can color observations or memories. Sometimes where a witness is standing and the quality of light can affect what the witnesses see (or think they see). Memories can be altered.

Sometimes witnesses lie.

That brings me to at least two witnesses in this case, Michael Cohen and Allen Weisselberg, who have recent histories of lying in official proceedings. Weisselberg is in jail right now for lying under oath in his testimony in Trump’s civil fraud case. In 2018, Cohen pleaded guilty to lying to Congress. Last month, on March 20, 2024, a federal judge suspected that Cohen lied again under oath. The judge denied Cohen’s request for early release from the court supervision, pointed out where he believed Cohen committed perjury, and said, “At a minimum, Cohen’s ongoing and escalating efforts to walk away from his prior acceptance of responsibility for his crimes are manifest evidence of the ongoing need for specific deterrence.” If Trump actually testifies, we will have three witnesses with histories of lying.

And that brings me to another overlap between litigation and literature: The unreliable narrator. An unreliable narrator is a first-person narrative told by an untrustworthy character. The reader of course figures out the truth. (A famous example is The Turn of the Screw.)

When unreliable witnesses give different versions in a trial, the jury decides what actually happened. I suspect in this trial we will have unreliable witnesses offering different versions of what happened. The testimony of unreliable witnesses can be strengthened with documentary evidence, which I suspect will also happen in this trial.

A Good Theory of the Case Makes Clear how the Facts Satisfy the Elements of the Crime (or rebut the elements of the crime)

Every crime is broken into elements. To get a conviction, the prosecution must prove each element beyond a reasonable doubt. The elements of falsifying business documents in the first degree are:

- The person makes or causes a false entry in the business records of an enterprise

- with intent to defraud that includes an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission of another crime.

The word “intent” is defined as a conscious objective or purpose. The “other crime” is the predicate crime.

Often (but not always) the predicate crime is charged along with falsifying business records. Bragg didn’t do that. If the predicate crime had been charged along with the crime of falsifying business records, we would have more clarity on the prosecution’s legal theory of the case.

Because there is a predicate crime, what the prosecution has to prove becomes more complex. The prosecution doesn’t simply have to prove that Trump falsified business records with an intent to cover up the hush money scheme to help him win the election. The prosecution also has to prove that:

- Trump’s part in the hush money scheme was a crime,

- Trump knew it was a crime,

- Trump falsified the documents, and

- Trump falsified the documents with the intent to cover a crime.

Other possibilities are open to the prosecutors, but this seems to be where the case is headed.

But Teri! If Trump denies he had a conscious objective or purpose, how can the prosecution prove what he was thinking?

Prosecutors prove intent and knowledge all the time. If there is no direct evidence (and there usually isn’t unless the defendant confessed) they use circumstantial evidence. The jury hears testimony from people who spoke to the defendant, examines the documentary evidence, and draws conclusions.

In the statement of facts accompanying the indictment, the prosecution describes the crime of falsifying business documents like this:

After the election, the Defendant reimbursed Lawyer A (Cohen) for an illegal payment through a series of monthly checks, first from the Donald J. Trump Revocable Trust (the “Defendant’s Trust”) a Trust created under the laws of New York which held the Trump Organization entity assets after the Defendant was elected President—and then from the Defendant’s bank account. Each check was processed by the Trump Organization, and each check was disguised as a payment for legal services rendered in a given month of 2017 pursuant to a retainer agreement. The payment records, kept and maintained by the Trump Organization, were false New York business records. In truth, there was no retainer agreement, and Lawyer A was not being paid for legal services rendered in 2017. The Defendant caused his entities’ business records to be falsified to disguise his and others’ criminal conduct.

I highlighted “illegal payment” because the statement of facts leaves out a few crucial details, including how Trump’s part in the hush money scheme was illegal and whether Trump knew his part was illegal. (If you have questions about what I mean, read last week’s post.)

The prosecution’s theory is generally simpler than the defense’s theory. In fact, when the prosecution presents its case, the theory is often so clarifyingly simple you’re likely to think, ‘Well that settles it.” Like this:

The defendant robbed the bank. As evidence, we present a videotape showing the defendant pointing his gun at the teller. You can see in the videotape that one of the four co-defendants handed the teller a note that said, “Put all your money in this bag.” We present the note as evidence.

See? You’re probably thinking, “Okay, well that settles it.” The case, in fact, always looks bleakest for the defendant after the prosecution rests its case. Then the defense has the chance to offer more details, like this:

In the video tape you can see that the other four co-defendants are surrounding my client. One stood to his right, one to his left, and two behind. What you can’t see in this videotape is that one of the co-defendants standing behind my client had a gun pointing at the defendant’s back.

We will present evidence that there is a long-standing rivalry between the defendant and the other four co-conspirators. The other four vowed revenge on my client because, the previous month, my client talked to the police and gave information about them.

So when the four co-defendants robbed the bank, they brought my client as a hostage, held a gun to his back, and forced him to take part in the robbery. Moreover, we will show that the four co-defendants have a long criminal history, this is my client’s first offense.

In other words, the defendant says, “Yes, I robbed the bank, but I did it under duress.” (Duress is an affirmative defense.)

My stepchildren were in elementary school when they asked about what I did as a criminal defense lawyer. The very idea had them confused. My stepdaughter (who now, incidentally, is finishing her 3rd year at Harvard Law School), asked, “Lawyers aren’t supposed to lie, right?”

Me: “Right. They are not supposed to lie.”

Stepdaughter: “Then how do you defend someone who is guilty?”

Me: “You know how it feels when you get in trouble and you just want to be able to tell the whole story: Why you did it, and that you’re still a great kid? Well, the defense lawyer tells the whole story.”

That satisfied her. Her brother, though, dug in and said, “Yeah but what if he’s guilty?”

(It turns out he did understand after all. The next time he got into trouble with his father, he said he needed a defense lawyer.)

In the Trump falsifying documents case, at this point, the prosecution’s theory of the case is more complex and fails to show how the facts satisfy the elements of the crime

The prosecution’s theory of the case (at this point) seems to be this:

Trump conspired (and intended) to interfere unlawfully with the 2016 election by concealing information that the voters might have considered. To do so, he repeatedly and fraudulently falsified New York business records to conceal criminal conduct that hid damaging information from the voting public during the 2016 presidential election.

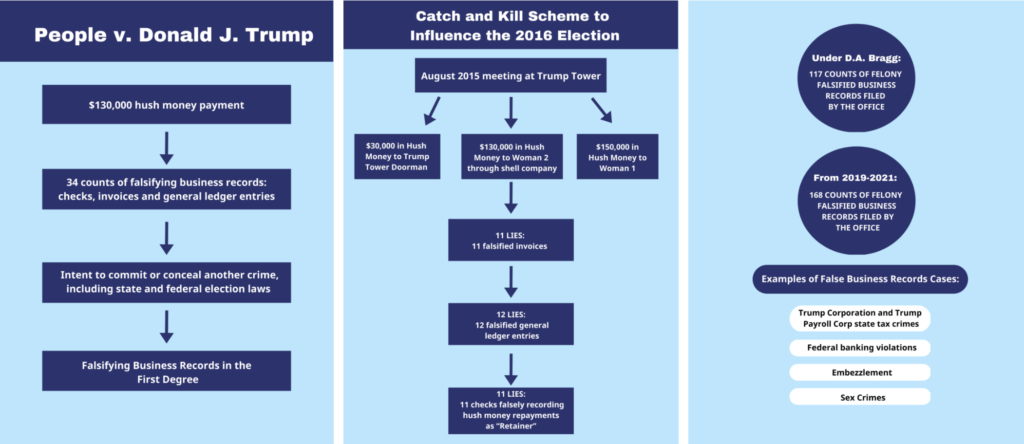

Bragg offered this chart to show the prosecution’s theory of the case:

The first two frames illustrate the alleged crime. The last frame shows that this crime is often charged, obviously to rebut accusations that the prosecution is politically motivated.

The prosecution’s theory of the case has the advantages of being compelling and establishing a motive.

The problem is that it fails to show how the facts meet the elements of the crime. Specifically, we are not shown facts that establish that Trump’s role in the underlying hush money scheme was illegal, and if it was illegal, that he knew it was illegal.

Because the chart and the theory of the case fail to explain how the facts satisfy the elements of the crime, I suspect this chart (and theory) was for public consumption.

In this chart, and in a public statement shortly after Trump’s arraignment, Bragg said that the concealed records scheme “violated New York election law, which makes it a crime to conspire to promote a candidacy by unlawful means.” But New York election law is not mentioned at all in the indictment or the accompanying statement of facts.

In other words, it isn’t completely clear what predicate crime Bragg will prove. Will he prove a violation of state election law or federal election law? He also offers this as a possible predicate crime:

The participants also took steps that mischaracterized, for tax purposes, the true nature of the payments made in furtherance of the scheme. (So far, from the facts, the only person we know of who benefitted from the tax help was Cohen.)

If Bragg ends up proving, as the predicate crime, that Trump falsified records to help Cohen commit tax fraud, the case will turn out not to be about election finance violations or election interference.

The Defense’s Theory of the Case

From something Trump said to reporters, this appears to be part of the defense theory of the case:

Trump did not falsify business records. Cohen performed legal services and incurred expenses as part of those legal services. Weisselberg and Cohen worked out the amount Cohen would be paid and presented the bill to Trump, who paid it. He recorded it as legal expenses because that’s what it was.

In other words, the theory is that there was no falsification of records. The expenses were legal expenses. This theory can be bolstered if Cohen’s “legal” practice with Trump was to “fix” situations, call it legal work, and then be paid a lump sum that included reimbursement for expenses. If, on the other hand, Cohen habitually itemized expenses, the theory falls apart.

Yes, there are also holes in this theory: There was no retainer, yet the bills were paid pursuant to a retainer. The services were performed in 2016 but the accounting said they were performed in 2017. Trump must have known these things were not true, so getting to falsified business records shouldn’t be too difficult.

The difficulty lies in the predicate crime.

This brings me to the second part of Trump’s theory of the case (which comes from this motion filed by Trump’s lawyers):

Trump was familiar with catch and kill arrangements, which are ordinarily not illegal. Keeping bad facts from voters is also not illegal. Michael Cohen, Trump’s personal lawyer, and Weisselberg, an accountant, worked out the arrangement to kill the stories and presented the bill to Trump. Because the lawyer and accountant involved didn’t tell him that a catch-and-kill arrangement in these circumstances was illegal, he had no way of knowing it was a crime, and in fact, didn’t know it was a crime. In a lawyer-client relationship, the lawyer is supposed to inform the client if the client is about to engage in illegal behavior.

Note: This is not an “advice of counsel” defense. The defense intends to use the fact that a lawyer was involved to negate Trump’s mens rea.

As I pointed out last week, not all participants in an illegal act have the same level of criminal liability. Because criminal liability requires a particular mental state (mens rea) it’s possible that not all people involved in an illegal scheme have criminal liability.

Thus the defense theory is in two parts, where each part rebuts one of the elements.

Element (1): The person makes or causes a false entry in the business records of an enterprise.

Defense theory: It was not a false entry. It was marked as legal expenses and that’s what it was.

Element (2): With intent to defraud that includes an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission of another crime.

Defense theory: Trump had no idea that the hush money scheme was a crime.

Not everything shady or immoral or wrong is a crime. Trump’s theory of the case seems to be: He knew he was hiding damaging information from the public to help with the election, which ordinarily isn’t illegal (candidates are not required by law to disclose every bad act they have committed). But Trump had no idea the hush money payments, which are usually not criminal, were criminal in this instance.

I suspect that once the trial starts, the prosecution’s legal theory will come into sharper focus and the defense’s legal theory will become more convoluted and garbled.

Well, Teri? How strong is the case against Trump? Will the prosecution win?

I will be in a better position to answer that question after I have seen all the evidence.

I suspect that Bragg has evidence that Trump knew the hush money payments constituted a crime or he wouldn’t have brought the charges and would not be framing this case as election interference. He is not a stupid man and he resisted Pomerantz’s push to bring the charges when he felt the case was not yet ready.

Can Trump be found guilty of misdemeanor (falsifying business records) if the jury doesn’t believe (beyond a resonable doubt) that he committed the predicate crime?

Yes. The misdemeanor (falsifying business records) is a lesser included offense. A lesser included offense is a crime that must be committed in carrying out a greater crime because the greater crime contains all of the elements of the lesser crime. In other words, before the defendant can be guilty of the greater crime (entering a false business record with the intent to defraud) the defendant must also be guilty of the lesser offense (falsifying the business record.)

A court may instruct a jury to convict the defendant on a lesser crime even if they are not convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant is guilty of the greater crime. So yes, Trump can defeat the felony charges but be found guilty of the misdemeanor charges of falsifying business records.

If Trump paid Cohen back, then Trump was using his own money. How can using his own money be a campaign finance violation?

There is no limit to how much candidates can contribute to their own campaigns, but the donations have to be reported. So yes, donating $130,000 to his own campaign and then hiding it would be a violation of federal election laws.

If Trump falsified the records after the election, how can the records be falsified as part of a scheme to interfere in the election? The election was over! Trump tried to postpone paying Stormy Daniels until after the election, when he could avoid paying her because once the election was over he didn’t care what people knew.

This is why the prosecution’s theory feels garbled. The election interference happened in 2016 and the payments were made after the election to cover the fact that Trump interfered in the election in 2016, even though, by the time Trump falsified the records, it wouldn’t matter if the public found out because he already won and he made clear that he didn’t care if the public knew what he did as long as they found out after he was elected.

On the other hand, Trump does not enjoy criminal prosecutions and he’d like them to go away, so his motive could have been to hide the payments, not as part of election interference but to hide his illegal behavior. Trump habitually hides his illegal behavior. Thus, by this reasoning, the case is not an election interference case. It is a cover your illegal tracks case.

I should have called this blog post Fun with Criminal Law. It looks like we will be having a lot more fun with criminal law in the weeks (and months) to come.

Subscribe and I’ll tell you when a new blog post is ready: