As I’ve been doing lately, this blog post started out as a 15-minute video. You can see it here. What follows is an edited transcript.

This week Senate Republicans voted to kill a bipartisan commission to look into the January 6th insurrection. They are also trying to outlaw teaching Critical Race Theory in schools. Critical Race Theory is an academic framework centered on the idea that racism is systemic, and not just demonstrated by individual people with prejudices. The theory holds that racial inequality is woven into legal systems. Laws banning the teaching of this theory in schools would be unconstitutional, but why would a detail like that stop the Republicans from trying?

Outlawing the discussion of slavery? Refusing to investigate an insurrection? What the heck is going on?

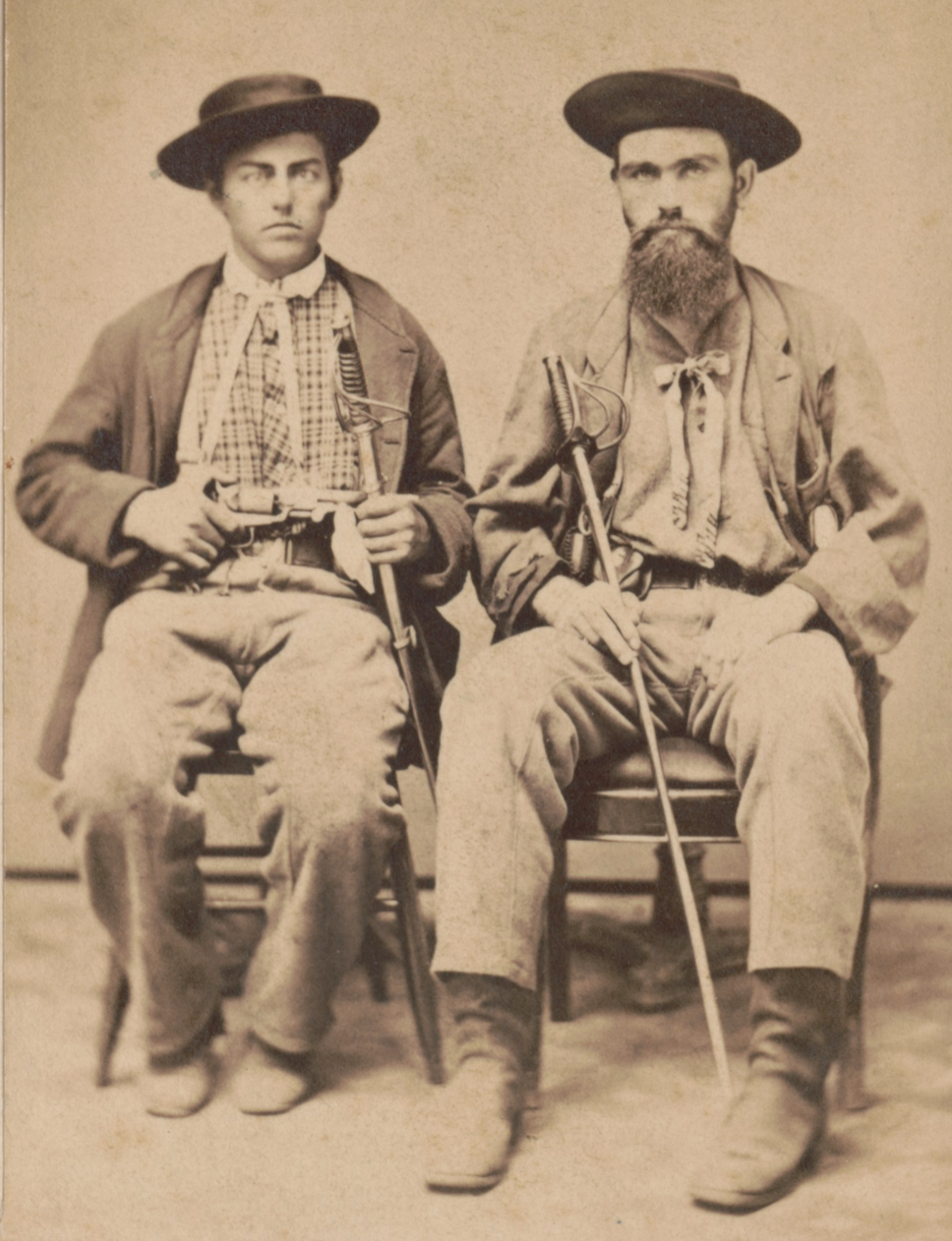

That’s easy. You see, these guys never went away:

(These were guys who went to Kansas to fight for Kansas to become a slave state.)

So it’s really no shock that one of our two parties is anti-democratic. There are lots of those guys, and they want a party, too. (The caption just says “Border Ruffians. I included the image in my biography of Lincoln, as part of my Making of America series.)

In a book called Demagogue for President, by Texas AM University professor Jennifer Mercercia explained how Trump used a set of well-known rhetorical strategies to awaken the sleeping Confederates and “border ruffians” and turned them into insurrectionists.

Mercercia’s book continues to be important because (1) Republicans who apparently want to be the next Trump are imitating these tactics and (2) Trump is continuing to use them in his defense and to keep control of the Republican Party.

Mercieca presents Trump as a master con artist. She says his gaffes weren’t gaffes. They were deliberate and masterful uses of aggressive debate tricks. She explains her use of the word “genius” in the title by saying Trump is a master at manipulating people through standard rhetorical devices. Basically she says he ingenuously wields communication as a force in a way that makes it difficult to respond to him.

I won’t march through all the devices. (It’s a long, comprehensive book.) But I’ll hit a few that most struck me.

First, what Mercieca calls “Appeal to the Crowd.” Basically, Trump tells his supporters that they’re smart enough to see through the manipulation of the “fake” media. He tells them America’s problems are not their fault; they’re the victims of corrupt and inept politicians. (All screenshots from Merceica’s book)

Next, she talks about Argumentum ad populum:

Argumentum ad populum (Latin for “appeal to the crowd”). Used by a demagogue to praise his or her supporters as wise, good, and knowledgeable. (P. 32, Kindle version)

Using this device, Trump — a liar and consummate salesperson—conned his supporters into thinking he was a truth-teller. He did this by positioning his “lack of political correctness” as “genuineness.” He positioned being “politically correct” as being “scripted” and going along with corruption.

His supporters bought it. The result was that the more outrageous Trump’s language became, the more “truthful” and less “corrupt” he appeared to be to his supporters. I know someone, actually, who voted for Trump saying, “He tells it like it is.” I asked, “He tells what like it is?” I got no answer.

From page 54:

Counterintuitively, perhaps, the more outrageous Trump’s language became, the more “truthful” and less “corrupt” he appeared to be to his supporters. Ultimately, for Trump’s loyal supporters, his ad populum strategy was a success.

Merceica says the impulse of Trump’s critics to mock him backfired by solidifying his position as a man of the people mocked by the establishment—a tricky feat for someone who claimed to be a billionaire real estate mogul.

“When Trump read the Muslim Ban in South Carolina,” recalled CBS News reporter Sopan Deb, “a lot of us assumed it would be a death knell to his candidacy. He had a lot of criticism coming at him from both parties. It was an unexpected proposal, and it received a lot of backlash, or so we thought. When he read it in South Carolina, he got a prolonged standing ovation.” (p. 73)

Trump’s “ad populum” argument during the primaries was annoyingly circular: “We know Trump is right because the people support him, and the people support Trump because he is right.”

Device #2 is one we heard Trump use repeatedly: Ad hominem. This was when Trump attacks his opponents’ character. The first thing to notice about this kind of thing is that attacking the person diverts attention away from the debated question. People focus on the attack. His critics assume that the very nature of the attack will reflect badly on Trump, but in the process, people entirely forgot the underlying criticism that prompted the attack.

For example, when Trump talked about the “highly untalented Washington Post blogger, Jennifer Rubin, a real dummy.” He went on to say she “never writes fairly about me. Why does Wash Post have low IQ people?” Who then remembers Rubin’s criticism of Trump? That’s completely lost because our attention is absorbed by the spectacle of a candidate for president talking that way about a well-known journalist. The device works, even if you don’t turn against Rubin because your attention was focused on the attack. Trump’s supporters, though, now know to ignore anything Rubin writes in The Washington Post because she treats Trump “unfairly.”

When other people tried to use this technique, if flopped. Remember when Marco Rubio tried to mock Trump’s small hands? He later regretted trying.

What some people call “projection,” Mercieca calls “appeal to hypocrisy.” It does always seems like Trump, and now the Republican leadership, accusing others of exactly what they do. People defending the insurrectionsts are saying that the Black Lives Protestors did the same, or worse. During the Mueller investigation Trump kept asserting without evidence that “there was no collusion except between Crooked Hillary and the Democrats.” This is a rhetorical device, which basically says “my critics have no standing to critique me because they have done it [or worse] themselves.”

And, third, ad hominem attacks can be based on the charge of tu quoque (appeal to hypocrisy), in which “an attempt is made to find a contradiction in one’s opponent’s words or between his words and his deeds.” (p. 36)

The user of this device is attempting to find a contradiction in one’s opponent’s words or between his words and deeds.

It’s worth noting that most people have the decency not to use or even consider using these kinds of rhetorical strategies. Using these techniques is aggressive, ugly, mean, and designed to destroy. Normal people just don’t do it.

The next rhetorical device I want to talk about is hugely important: Paralipsis, which may be the vocabulary word of the decade. It means saying something while claiming not to be saying it. Here’s an example:

For example, “I’m going to be nice today,” Trump said at a rally in Birmingham, Alabama, on November 21, 2015. “I’m not going to call Jeb Bush ‘low energy’; I’m not going to repeat it. I’m not going to say that ‘Marco Rubio is a lightweight.’ I said I’m not doing it! I will not do it. I will not say that ‘Ben Carson had a bad week.’ . . . I said that I’m not going to say it, so I’m not saying it! So, I’m not saying any of those things about any of those people.” (p. 83). Kindle Edition.

A less playful example during the 2016 campaign was when Trump retweeted an unnamed lawyer explaining how Rubio and Cruz couldn’t become president because they weren’t “natural born citizens” of the United States. Later, he insisted he wasn’t accountable because all he did was retweet something.

“I mean, let people make their own determination. I’ve never looked at it, George. I honestly have never looked at it. As somebody said, he’s not [eligible]. And I retweeted it. I have 14 million people between Twitter and Facebook and Instagram, and I retweet things and we start dialogue and it’s very interesting.” (p. 83).

This gives Trump deniability. It lets him spread innuendo without accountability.

More recently, after calling his supporters for a Stop the Steal rally, and after riling them by telling them that the election was being stolen and Pence had the power to stop it, Trump told his supporters at the “Stop the Steal” rally to “fight like hell,” and then pointed them to the Capitol. He also said, “Be peaceful.” When they did fight like hell, Trump said that he didn’t mean “fight” literally because he said “peaceful,” and besides, Elizabeth Warren says, “Fight” all the time. Notice, this is basically the same defense that Giuliani put forward, which I talked about last week. I said it but I didn’t say it. I said it, but I didnt really mean it.

One of my followers on Twitter gave this example of paralipsis:

“I’m not saying she needs to lose a few pounds, but . . . “

Trump’s followers and supporters feel like they’re in on his jokes. They applaud his deliberate ambiguity, which they understand lets him escape accountability. Here’s how a fan responded to Trump’s disavowal of white supremacy. When confronted by the fact that David Duke supported Trump, he said: I love it when Trump plays dumb,” said one Vanguard News Network poster in response to Trump’s comments on Duke.

Basically, Trump unleashed the ugly. He awakened the sleeping Border Ruffians, gave them permission to be racists and ugly, and turned them into insurrectionists:

Trump’s supporters could participate in the pleasure of violating the norms of political correctness and fighting corruption by championing their hero and using language like he did. Spreading Trump’s messages and attending Trump rallies allowed Trump’s fans to be politically incorrect without repercussion. Trump campaign rallies became “safe spaces” for Trump supporters to say whatever they had been suppressing due to the scourge of political correctness.12 News reporters described hearing violent and sexist slurs against Hillary Clinton and chants of “TRUMP THAT BITCH!” (and worse) at Trump rallies. Reporters described hearing obscene, racist, and homophobic slurs regularly, in fact. On August 3, 2016, the New York Times posted a video showing the “very inflammatory, and often just plain vile, things that many people showing up to support Mr. Trump’s campaign were saying out loud—often very loudly—or wearing on their T-shirts and hats.”13 The video began with Trump declaring, “You know, the safest place in the world to be is at a Trump rally,” to which the crowd responded, “Build the wall! Build the wall!” while someone shouted, “Fuck those dirty Beaners.” In another clip, Trump said, “Our president has divided this country so bad,” to which someone in the crowd responded, “Yeah, fuck that nigger!” (p. 52).

Observation: Marjorie Taylor Greene, Rep. from Georgia, thinks that the way to imitate Trump is to be as vulgar as possible and try to create the maximum amount of outrage, but what we get from Demagogues for President is that successfully deploying these devices is a skill that not everyone possesses. It seems to me that Greene lacks Trump’s evil genius for manipulating people.

Other devices from the book include Exceptionalism. “America is the greatest but our enemies within have weakened America. I alone can fix it.”

And this

American exceptionalism (America’s unique status among other nations in the world). Used by a demagogue to motivate audiences to support the demagogue’s policies. (p. 36).

Reification (from the Latin “rēs” for “thing”—thingification, treating people as objects). Used by a demagogue to signal that a demagogue’s designated enemies are unworthy of fair treatment.82 “All reification is a forgetting,” wrote Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, because reifying rhetoric allows speakers to “forget” that people are not things, that people have immanent value (that they have value qua people as opposed to value qua utility or capitalism). (p. 40).

If you’ve studied fascism and fascist tactics, you’re probably saying, “Wait! I’ve seen all this before.” It’s easy to see the overlap between these rhetorical strategies and fascist tactics as outlined by scholars like Jason Stanley.

For example, some of the rhetorical devices Mercicica describes are designed to unify his supporters and increase the polarization between his supporters and everyone else. Jason Stanely describes fascist tactics as creating an “us v. Them” politics. One of Stanley’s points, in fact, is that Trump is cynically using a set of fascist tactics to seize and maintain power.

There is a striking similarity between the rhetorical strategies Merceica describes and fascist tactics. Fascists dehumanize the “enemies” (reification). Nazis called Jews “vermin,” which led to “extermination.” Fascist leaders create spectacle. See, for example, this post. Mercieca explains that these rhetorical strategies are designed to do just that.

A second effect of the spectacle was to silence opposition, prevent logic and critical thinking, and inculcate distrust, since without critical thinking “no one can be sure he is not being tricked or manipulated.” The spectacle “silences anything it finds inconvenient. (p. 288).

No surprise! Fascist leaders are also masters at these techniques. Fascist leaders also lack the moral compass that allows them to use these strategies. Scholar Robert Paxton, in his book, Anatomy of Fascism, said that the world’s first fascists were not Italians under Mussolini. They were the Ku Klux Klan in the South. They even had their own “uniform” or identifying piece of clothing, those white sheets. Fascists like identifying items of clothing. MAGA hats, anyone?

So what do we do? Educating the people to recognize these tactics will help:

Perhaps the best way to neutralize a dangerous demagogue is also the most democratic way: to let the demagogue’s audience in on the demagogue’s strategic game so they can decide for themselves what they think about it (as I have done throughout this book). (p. 285).

But, as Mercieca points out, educating people is tricky because these rhetorical devices are specifically designed to prevent people from using critical judgment. Also there are people who eagerly embrace the rhetorical strategies as a means to destroy. But for most people , a book like this one helps. It’s helpful to have a name like parelipsis to describe what we’ve been seeing.